Damion Smy

Porsche reveals its most powerful 911 ever

7 Days Ago

Contributor

It might surprise you to learn Ford didn’t intend the Mustang to compete directly with muscle cars of the day when it launched in 1964.

At the time, American muscle cars had a distinct formula: a long, heavy body paired with a V8 engine driving the rear wheels. They were expensive vehicles that often sat atop top a manufacturer’s range, and compromised cornering and handling ability for straight line speed.

With models such as the Thunderbird, Galaxie, and Fairlane, Ford already had several options in the late 1950s and early 1960s that fit that description.

But with America’s economy rapidly recovering after WWII and the first of the baby boomers moving out of home, Ford predicted there would be demand for a stylish but inexpensive sports car that retained a modicum of practicality.

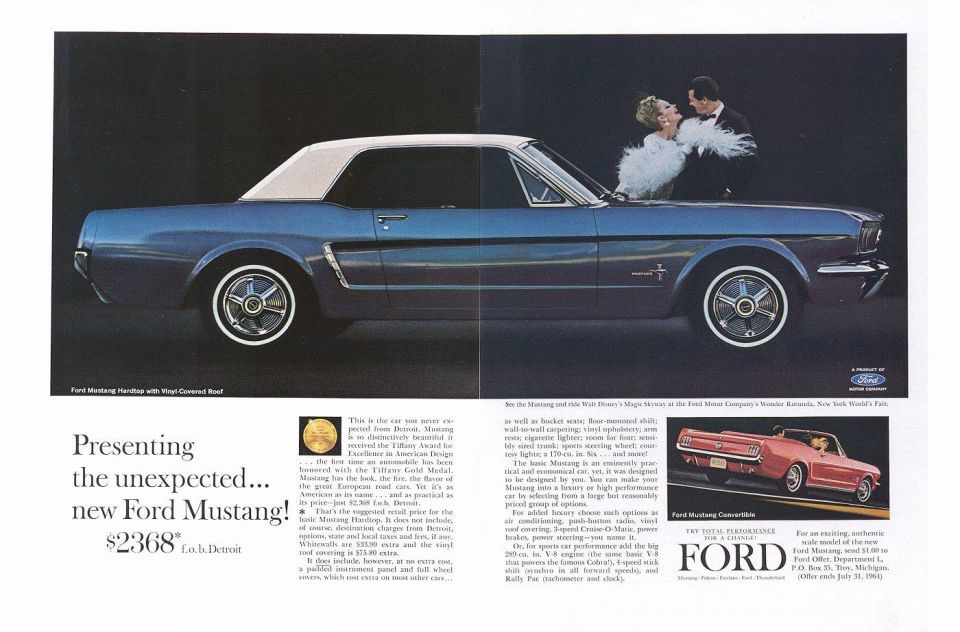

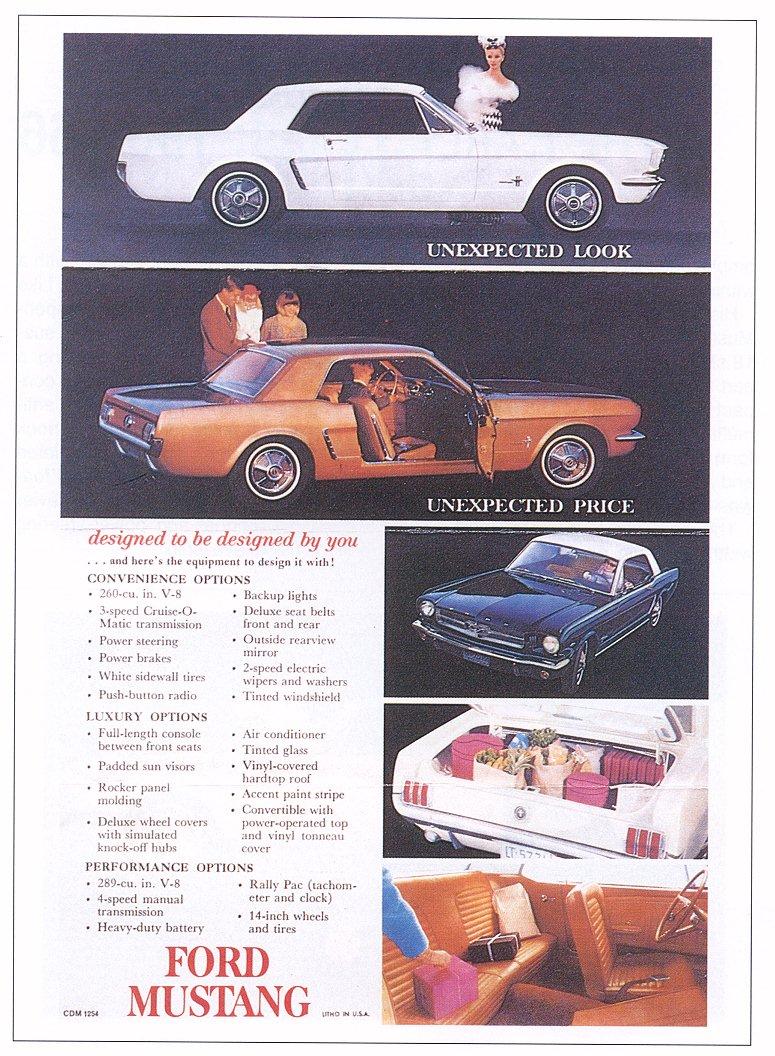

The Mustang was the result. Launched on April 17 at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, it was shown as a convertible and a three-door hardtop, both with seating for four.

Underneath, both versions used a bog standard Ford Falcon chassis (which at the time was a midsize sedan, equivalent to a modern Toyota Camry) paired initially to a weedy 2.8L (170 cubic inches) six-cylinder engine offering just 75kW of power.

A wider range of more powerful engines was soon available, but the Mustang was an instant hit nevertheless. Ford predicted annual sales of approximately 100,000 units. With a starting price of US $2368 (approximately AU$26,000 today), Ford received 22,000 orders on launch day alone, and had sold 1 million examples within the first two years of production.

Even car rental company Hertz wanted a slice of the Mustang pie, ordering several high performance Shelby GT350 examples that could be rented as track cars.

The Mustang was successful enough to create a class of its own, the ‘Pony Car’, and soon fielded direct competitors, most notably the Chevrolet Camaro.

The Falcon platform was not an especially sporty foundation to build upon, but the link between it and the Mustang was unavoidable with the two models sharing an identical length, and similar wheelbase and track.

Interestingly for a car offered as both a hardtop, convertible and later as a fastback, Ford developed the open-top variant first to ensure that it had adequate stiffness, before proceeding to engineer the other body styles that would be naturally stiffer with a roof.

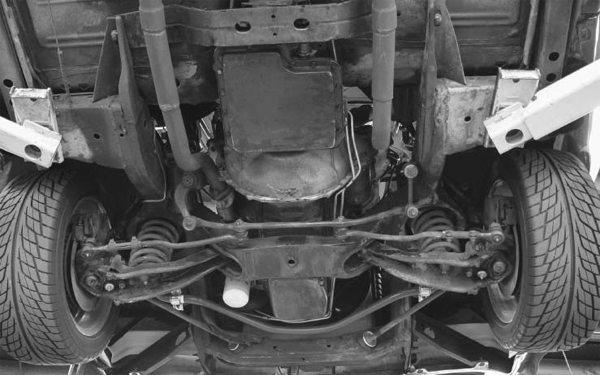

The key innovation here was the industry-first adoption of torque boxes to improve rigidity. As implied by its name, the torque box worked to transfer torque across different parts of the chassis and suspension, to prevent the chassis from twisting.

Convertible Mustangs featured a set of front and rear torque boxes. The front torque boxes connected the front frame rails and rocker panels, and acted as a gusset that strengthened this part of the unibody to the extent forces transmitted from the wheels and suspension would cause the chassis to flex less, and improve handling by reducing roll.

Similarly, the torque boxes at the back were located in front of the Mustang’s rear leaf spring suspension and served to spread the forces transmitted from the car’s driven wheels more evenly through the chassis, aiding in those all-important drag race launches and improving general rigidity.

Later hardtop and fastback models would also gain these torque boxes, where the additional bracing they provided also improved crash safety in the event of a side impact.

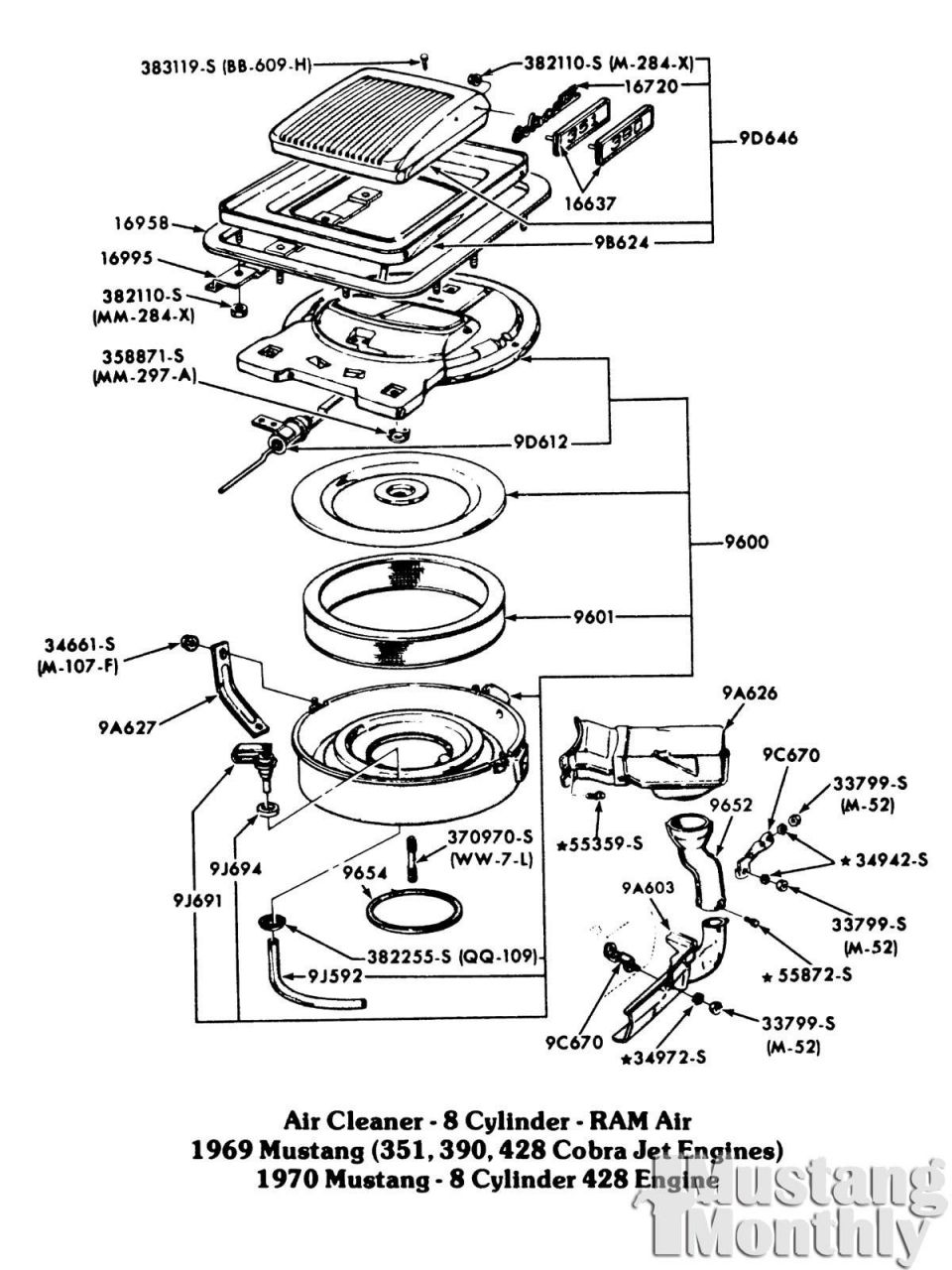

First generation Mustangs produced from 1968 onwards also featured the powerful and infamous 428 cubic inch (7.0L) Cobra Jet engine with ram air induction, officially rated at 335hp (250kW) to comply with the US Super Stock drag racing classification, but tested by enthusiasts and automotive publications alike to produce around 410hp (300kW).

Apart from the cool name, ram air induction manifested itself through the use of functional bonnet scoops. Similarly to sophisticated supercharging and turbocharging technologies, ram air induction aimed to improve power by increasing airflow into the engine.

Unlike those technologies, however, ram air induction was a passive system. When the car was driving at speed, the bonnet, bonnet scoops, and front of the car would work to sculpt the air, creating a pressure wave that force fed air through inlets in the bonnet scoop to the engine.

As more air was introduced into the engine, the carburettor would provide greater fuel to maintain a consistent air/fuel ratio, thereby increasing power.

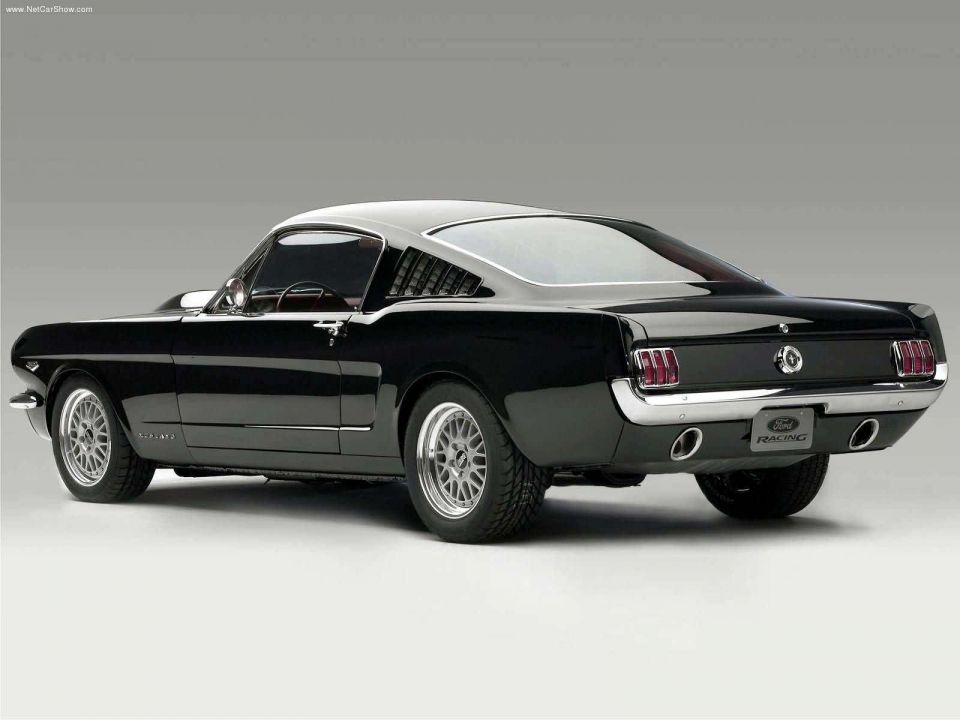

Apart from providing affordable performance, the Mustang’s design was a key reason for its sales success. Regardless of body type the Mustang had cab-rearwards proportions, with a long bonnet and short rear deck lid ideal for a sports car.

The hardtop in particular featured an upswept kick along the side profile to create a more prominent shoulder that emphasised the car’s performance.

All models featured distinctive design details inside and out such as tri-bar taillights, a deep dish steering wheel, and a cockpit-style double cowl dashboard to enhance the feeling that the Mustang was a driver’s car.

Personalisation was also an important aspect of the Mustang design and ordering process. The car came standard with not much else apart from a padded dashboard and wheel covers; everything else from a centre console, to power steering and brakes, seat belts and air conditioning were optional, with further customisation also available through numerous paint options, the addition of racing stripes and of course different engines.

All of this served to increase profitability, as it was rare for a customer to simply pay the advertised list price. Most chose to instead spend hundreds more on desirable options and other mechanical upgrades.

Where expert car reviews meet expert car buying – CarExpert gives you trusted advice, personalised service and real savings on your next new car.

Damion Smy

7 Days Ago

Derek Fung

8 Days Ago

Max Davies

10 Days Ago

William Stopford

14 Days Ago

Marton Pettendy

14 Days Ago

Damion Smy

14 Days Ago