William Stopford

The CarExpert team's favourite reveals from the Munich motor show

11 Hours Ago

Contributor

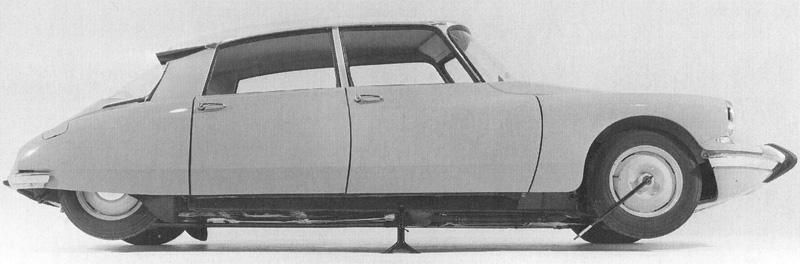

France is famed for its revolutions, and French carmaker Citroën was no stranger to the party with the launch of its DS in 1955. A technological tour-de-force, the DS debuted innovations that were decades ahead of its time, some of which remain impressive today.

It proved that French engineering at its best truly could be world class, and firmly established Citroën as an expert manufacturer of cars with that coveted magic carpet ride.

With a name that played on the French word for goddess, Déessee, the DS proved its mettle as a divine harbinger of good fortune when it helped French President Charles De Gaulle survive an assassination attempt in August 1962.

Despite a hail of over 100 bullets puncturing all four tyres, the DS was able to speed away to safety due to its innovative suspension system.

Although the DS is renowned most for this suspension system, the car brought impressive advances in everything from aerodynamics and material design to vehicle safety.

Citroën sold approximately 1.5 million examples of the DS over a 20 year lifespan, and today the model acts as a spiritual ancestor for Groupe PSA’s ‘DS’ luxury brand, which unfortunately hasn’t yet replicated the technical advances of the original DS within a modern context.

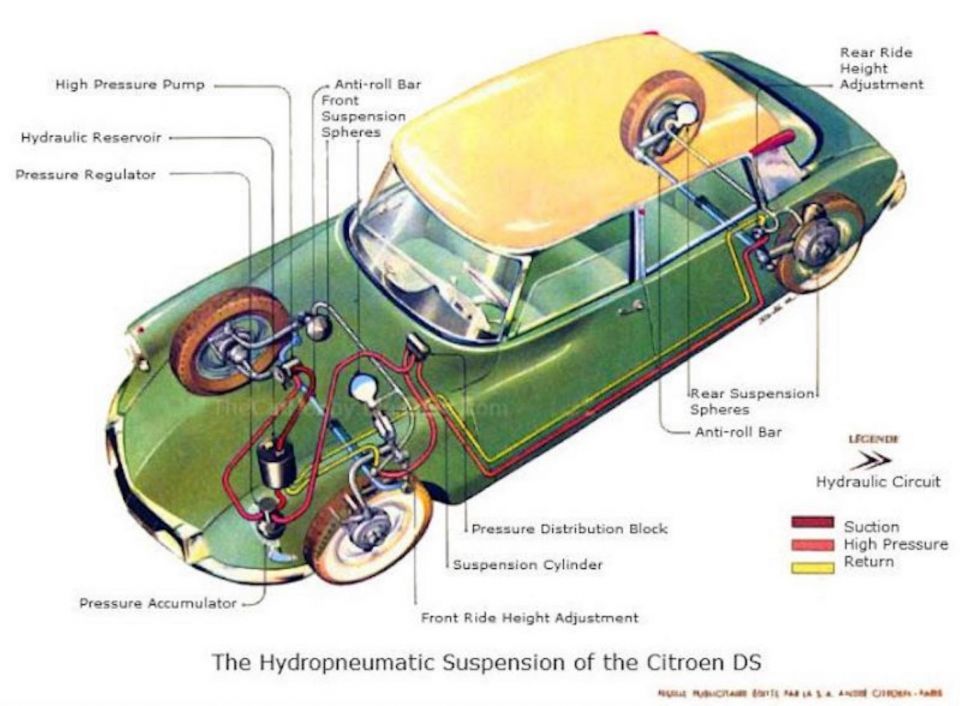

The DS was most renowned for its advanced use of hydraulics, especially its innovative hydropneumatic suspension system.

The system took advantage of the fundamental scientific principle that a gas is far easier to compress than a hydraulic fluid, with the DS applying this through the use of spheres that replaced the traditional steel coil spring and damper assembly.

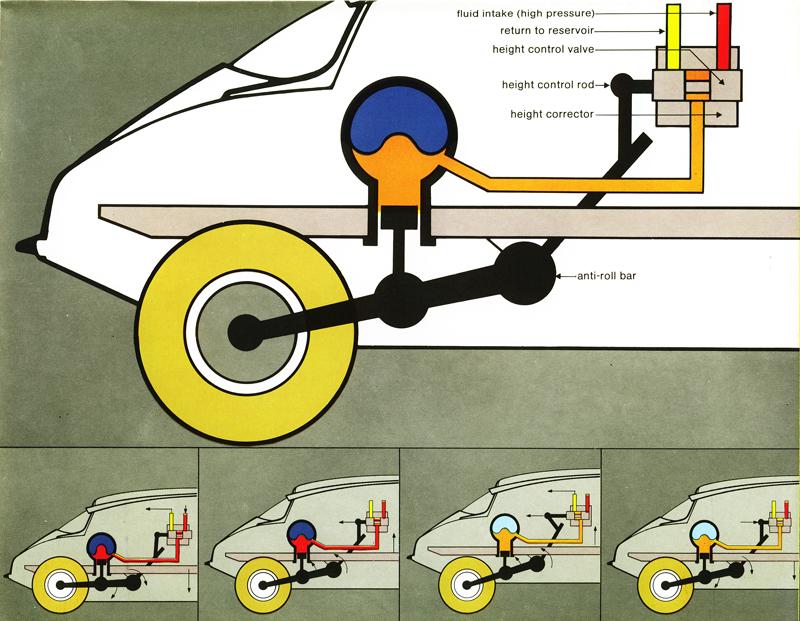

Each sphere was pressurised, with the top half being filled with nitrogen gas and the bottom half being filled with hydraulic fluid, and separated by a rubber membrane. The DS used one sphere per wheel, alongside an accumulator sphere that contained an additional reserve of hydraulic fluid and helped to equalise pressure across each sphere. A piston connected each sphere to the wheel.

Confronted with a bump, the upwards wheel movement shifted the connected piston further into the sphere, pushing in a greater amount of hydraulic fluid. The volume of the nitrogen gas was reduced, with a corresponding increase in gas pressure.

The overall effect was to create a progressive spring rate, similar to the more simplistic Hydrolastic system later used on the Mini.

The spheres allowed the suspension to provide a self-levelling ride that balanced between comfort and handling with minimal body-roll and dive under hard braking. The same amount of suspension travel was available regardless of the vehicle load (i.e. weight of passengers and luggage onboard).

The use of pressurised hydraulic fluid also offered numerous secondary benefits. Foremost was a variable ride height that could be raised or lowered to facilitate easier loading and unloading of luggage.

Its variable ride height and self-levelling ability of the suspension meant that the DS was also one of the first cars that that didn’t require a jack to change a flat tyre.

The transmission made use of a hydraulically operated clutch and gearshift to create a semi-automatic transmission, largely unheard of in 1955. Practically, this meant that whilst the driver had to manually shift gears (using a column mounted gearstick) and blip the throttle whilst doing so, there was no heavy, separate clutch pedal and the car could not be stalled.

Rather than a conventional lever-style brake pedal, the brakes in the DS were operated via a squeezable, mushroom-shaped button. The greater the pressure applied, the greater the braking force.

Nevertheless, adjustment was required from drivers due to the slightly different response compared to a regular brake pedal.

It’s well known in nature a teardrop shape is the most aerodynamically efficient, and the sailboat styling of the DS used this to great effect. The concealed underbody, smooth side profile with enclosed rear wheels, sloping tail, and lack of a front radiator grille helped create in a coefficient of drag of just 0.355.

Another factor aiding aerodynamics was the fact that the car was wider at the front than at the rear, with the uneven track widths not only developing a true teardrop shape and improving manoeuvrability, but also mitigating the understeer typical of front wheel drive vehicles.

The DS employed two innovative design techniques to improve vehicle dynamics. A lightweight fibreglass roof was used to lower the car’s centre of gravity, similar to how performance cars today are offered with carbon-fibre roofs.

Secondly, the DS made use of inboard brakes that were mounted on the vehicle chassis rather than the wheels to reduce unsprung weight, allowing for improved handling.

In addition to the innovations described above, the DS pioneered a number of safety improvements throughout its lifecycle.

Upon its launch in 1955, it was one of the first vehicles to come standard with inboard front disc brakes, a significant improvement at a time when drum brakes were the norm for all four wheels.

It may seem minor today, but steering wheel design could have a significant impact on the likelihood of sustaining an injury in a time when seatbelts weren’t commonly worn.

The DS is famed for its single spoke steering wheel which, rather than being different for the sake of it, provided a safety benefit as well.

Typical steering wheels at the time made use of a straight central column, which in a frontal impact ran the risk of spearing the driver. The Citroën DS design used a hollow spoke that curved away from the driver, so that in a collision, it would be more likely to slide over the body.

Another safety technology introduced with the DS later in its life was directional headlights, so the inner high-beam headlight turned in conjunction with the steering wheel.

The system worked so the headlights would turn to a greater degree than the steering itself, allowing the system to illuminate turns before the car travelled through them.

Where expert car reviews meet expert car buying – CarExpert gives you trusted advice, personalised service and real savings on your next new car.

William Stopford

11 Hours Ago

William Stopford

11 Hours Ago

Andrew Maclean

12 Hours Ago

Derek Fung

12 Hours Ago

Andrew Maclean

12 Hours Ago

Ben Zachariah

1 Day Ago