Max Davies

2026 Ram 1500 Rebel review

5 Days Ago

Unlike fuel tanks, the capacity of a battery gradually degrades over time. Here are some ways to maximise the lifespan of your EV’s battery

Contributor

Contributor

Electric vehicles may have first been produced over a century ago, but EV battery technology in particular has advanced in leaps and bounds over the last few years.

EVs of late have seen significant advances in range and fast charging capability, often at a comparable price.

Unlike a combustion-engine car where it doesn’t matter whether the car is refuelled from completely empty to full, charging your EV from zero to 100 per cent is generally not a good idea. Although dependent on the specific chemistry, the batteries in many EVs can be sensitive to how much and how often they are charged.

The majority of EVs available for sale today continue to use an NMC (nickel-manganese-cobalt) lithium-ion battery chemistry, and these types of batteries have a ‘sweet spot’ with regard to the battery’s state of charge in order to minimise battery degradation.

Generally speaking, this range is from 20 per cent to 80 per cent, such that during everyday driving, the battery’s state of charge should not exceed 80 per cent of its total capacity, and shouldn’t drop below 20 per cent either.

Effectively, this means that in day-to-day use, it’s safe to assume that the usable range of an EV may be the equivalent of 60 per cent of its total battery capacity. Of course, charging to 100 per cent for the occasional road trip or other long distance journey is perfectly reasonable, and shouldn’t have a substantial impact on battery longevity.

Some EVs, especially those originating from China such as the entry-level (single motor) Tesla Model 3, use a different type of lithium-ion battery chemistry, namely LFP, also known as lithium-iron-phosphate.

MORE: Electric car battery chemistry: What’s the difference?

In this particular case, Tesla suggests that regularly charging the car to full will have zero impact on battery life. Other EVs that also make use of an LFP battery may or may not have similar advice for their owners.

Another factor that may affect battery longevity is frequently making use of DC fast charging, as often found at public EV fast charging stations (also commonly referred to as Level 3 charging).

DC fast charging results in high currents being created within the battery, which in turn increases the battery temperature, burdening it with additional strain that could degrade the longevity of the battery.

Arguably the key takeaway here is that charging your EV’s battery at a DC fast charging station should be done sparingly, and used to quickly ‘top-up’ the battery, rather than being solely relied upon to charge your battery from empty to full.

Instead, charging your vehicle overnight through slower AC charging (Level 1 and Level 2 charging, if available at your residence) should be the primary way to charge your electric vehicle. This also carries the added benefit of allowing you to leave home each morning with a full charge.

Some newer EVs come with an advanced form of battery pre-conditioning, that may further reduce any longer-term impacts associated with frequently using DC rapid charging stations.

If the driver uses the car’s in-built GPS system to navigate directly to a fast charging station, the car will automatically begin cooling or heating the battery as appropriate given the ambient temperature and other environmental conditions to ensure it is at the optimal temperature by the time it arrives at the charger.

This may not only reduce stresses on the battery and thereby maximise its longevity, but could also reduce charging times as the battery temperature doesn’t have to be significantly raised or lowered after the car is plugged in.

Regardless of how you charge the battery of your EV, most carmakers provide a dedicated battery warranty that is separate from the warranty covering the remainder of the vehicle’s components.

The current industry standard for EV battery warranties is eight years or 160,000 km, whichever comes first. In most cases, the manufacturer will guarantee that the battery will retain at least 70 per cent of its original charging capacity over this time period.

Of course, some manufacturers do vary slightly from this norm. BMW, for example, covers the batteries of its electric vehicles to eight years or 100,000km, while Nissan’s refers to a minimum retention of ‘9 bars out of 12’ (i.e. 75 per cent) for its Leaf.

Meanwhile, Tesla exceeds the industry threshold with its Model 3 in Long Range and Performance guises, with each of these variants guaranteed to eight years or 192,000 km.

Perhaps a key development in this space are the EVs that have been developed on Toyota’s new dedicated electric vehicle platform, e-TNGA, namely the Toyota bZ4X, Subaru Solterra and the upcoming Lexus RZ.

For the bZ4X in particular (but likely to be applicable to other e-TNGA cars), Toyota has claimed that it’s aiming for the battery to retain 90 per cent of its original charge even after 10 years or 240,000 km of use, a substantial improvement on the battery warranties offered by most electric vehicles today.

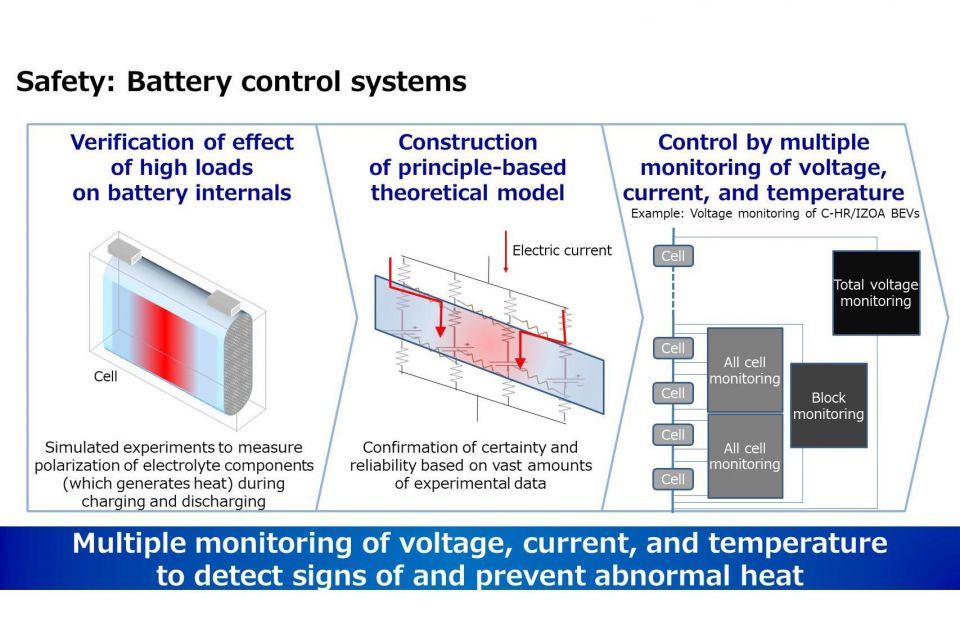

The Japanese marque claims this will be possible by monitoring the temperature of individual cells that comprise the battery pack, to detect any localised instances of abnormal heating, and then adjusting the battery’s cooling system to compensate for this.

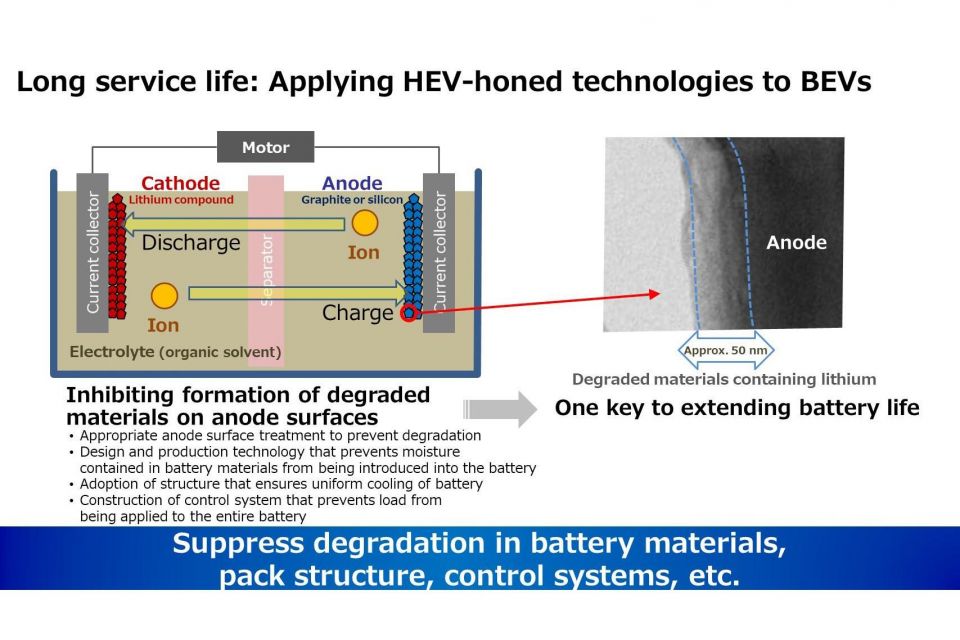

Toyota will further support this through other innovations such as minimising the degradation of materials on the surface of the anode, and improving the quality of the manufacturing process to reduce the instances of metallic foreign matter connecting the battery anode and cathode.

Max Davies

5 Days Ago

Max Davies

4 Days Ago

Neil Briscoe

3 Days Ago

Max Davies

2 Days Ago

Alborz Fallah

13 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

12 Hours Ago