James Wong

2026 Audi SQ5 review: Quick drive

6 Days Ago

News Editor

Whether you pronounce it “Zee” or “Zed”, there are few Japanese car names more evocative than that of the Nissan Z-Car.

The new Nissan Z is being revealed tomorrow at 10am, Australian time. We’ll have plenty of coverage on the car when it’s launched, but in the meantime let’s take a walk down memory lane.

In almost continuous production since 1969 – but for a brief gap between the second 300ZX and the 350Z – the Z nameplate predates myriad memorable Japanese sports coupes, from its arch-rival the Toyota Supra (1978) to fallen comrades like the Toyota Celica (1970) and Honda Prelude (1978).

It is, however, as old as another legendary nameplate: the Nissan Skyline GT-R, which also commenced production in 1969.

Japanese readers will know the Z by an additional name: Fairlady. In a land of cars with names like Cedric and Bongo Friendee, Fairlady fits right in. The eccentric name first appeared on a Datsun roadster in 1960, and when production of the first Z-Car began it wore Fairlady Z badging in its home market.

MORE: Meet the Nissan Z Proto

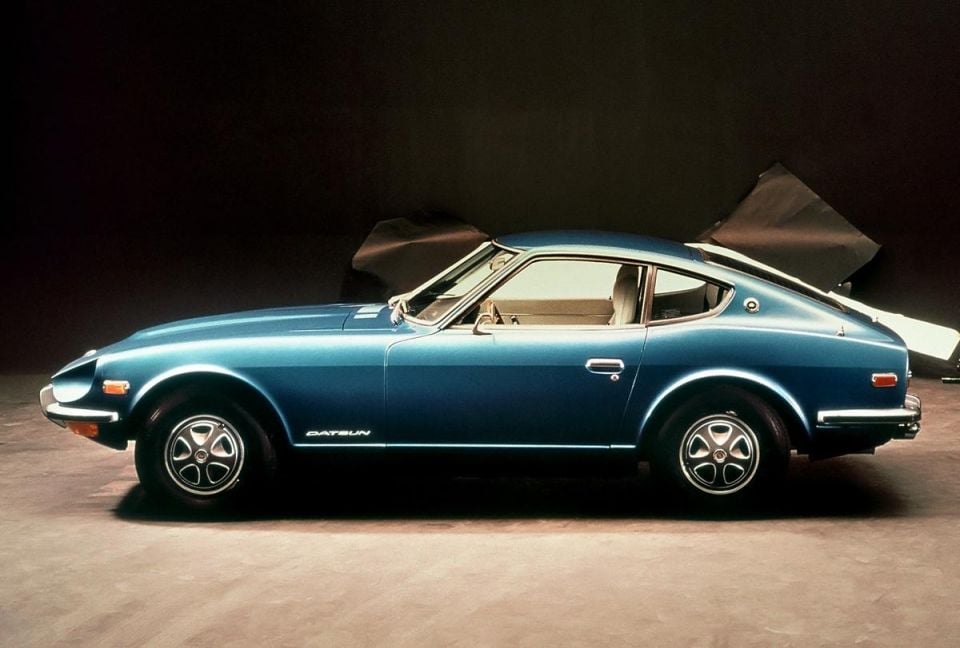

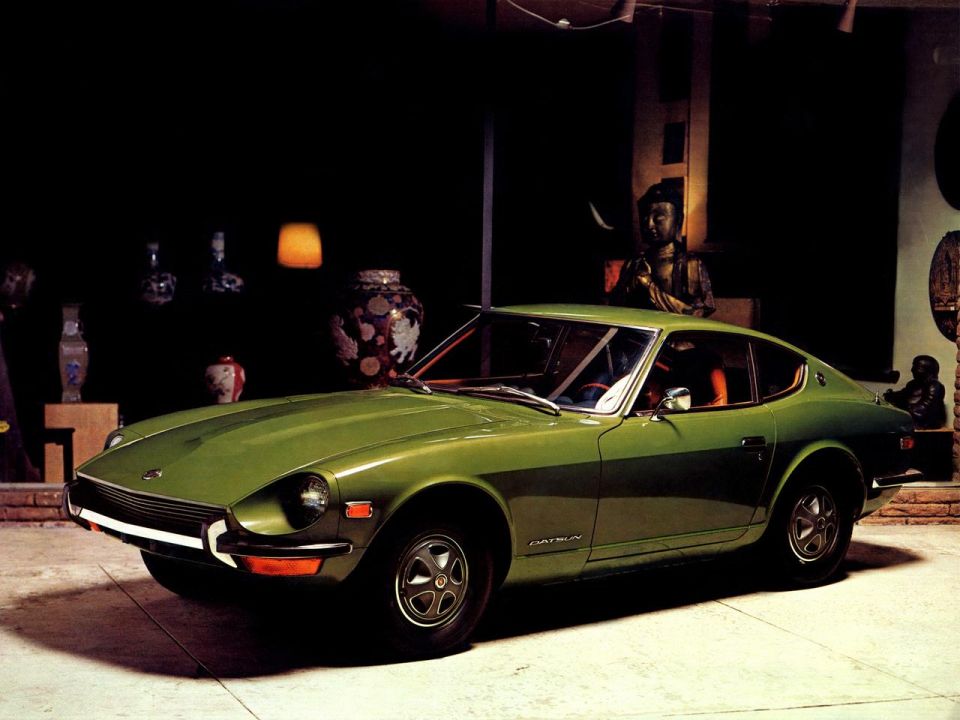

The Z story began with the 240Z, and what a compelling first chapter it was. While Datsun had been making small, sporty vehicles for a decade or so, the 240Z was arguably the car that well and truly put it on the map in the global sports car market.

The stunning 240Z was designed by a team led by Yoshihiko Matsuo. It wasn’t the first gorgeous sports coupe to come out of Japan but, in contrast with the Toyota 2000GT, the 240Z was accessible to more buyers.

At the time of its launch in Australia, it cost $4567. For context, that was a good deal more expensive than a Ford Capri GT 3.0 ($3230), Holden Monaro GTS 307 manual ($3673) or a Triumph GT6 ($3865), but it undercut the BMW 2002 ($4800), Lancia Fulvia 1.3S ($4870) or Volvo P1800 ($6995). It was also half the price of the cheapest Porsche 911.

For that money, you didn’t just get sensuous styling. There was also four-wheel independent suspension and a 2.4-litre overhead-cam inline six-cylinder engine mated to a five-speed manual transmission. A three-speed automatic arrived the following year.

There may have been more variety in the sports coupe market in the early 1970s than today but the 240Z nevertheless stood out, with American consumers in particular taking an immediate shine to this slinky coupe.

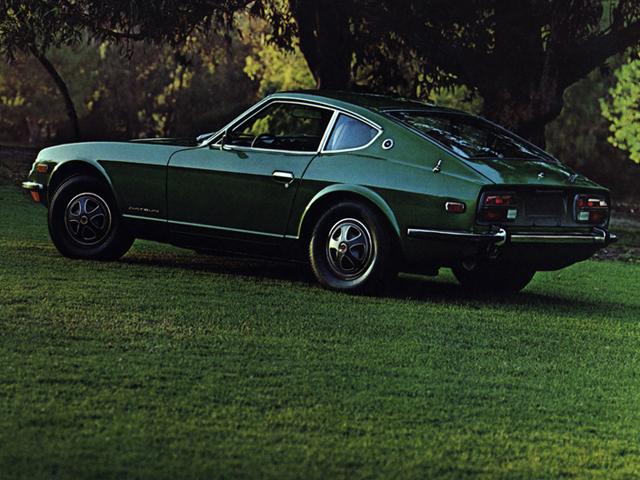

With the 260Z, Datsun conceded some buyers might want to carry an additional couple of (very small) people in their Z-Car. Therefore, it introduced a new 2+2 model with a 304mm longer wheelbase, which would be sold alongside the existing two-seater.

Otherwise, the 260Z was a subtle evolution of the original Z. That included a larger, 2.6-litre inline six as well as a new dashboard and some tweaks to the suspension. While a 280Z arrived in North America in 1975, the 260Z continued in all other markets until the introduction of the 280ZX.

As the name suggests, the 280Z featured a bored-out, fuel-injected version of the 260Z’s inline six displacing 2.8 litres.

Datsun was no longer exempt from new US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration bumper standards, which mandated bumpers that could withstand an impact of 5mph from the front (1973) and rear (1974).

The new bumper standards, which were mostly rolled back in 1982, had a detrimental effect on the styling and, in some cases, the handling of vehicles – witness the MG B, which had to have its ride height increased to meet the standards and suffered from ungainly black bumpers.

Unfortunately, the 280Z’s bumpers looked like giant railroad ties, while the more powerful, fuel-injected inline-six didn’t make the car any faster due to the mandated emissions equipment.

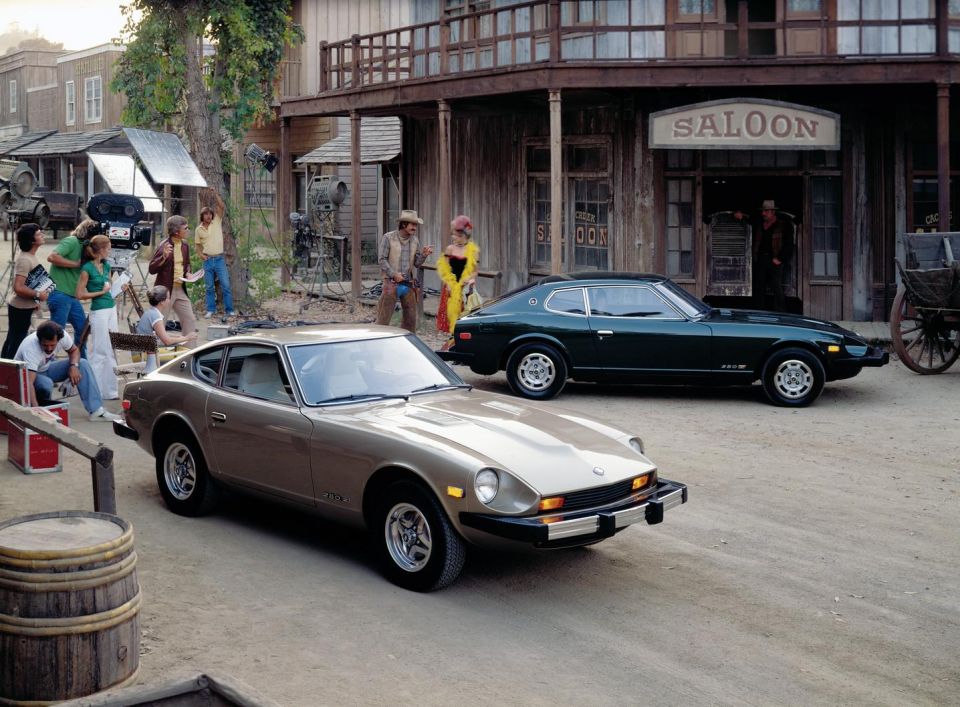

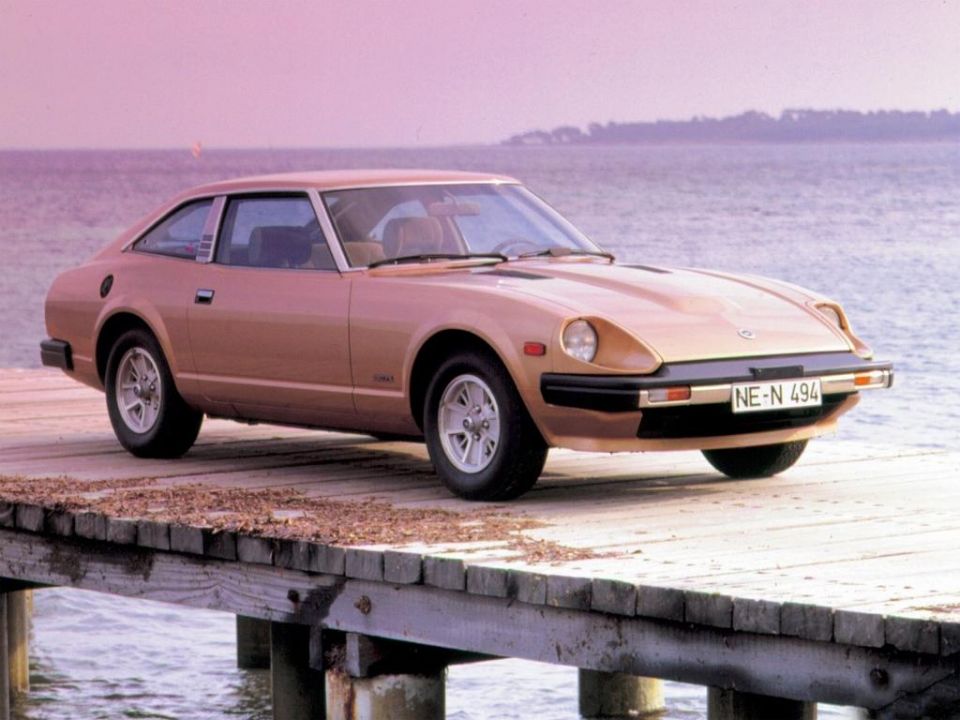

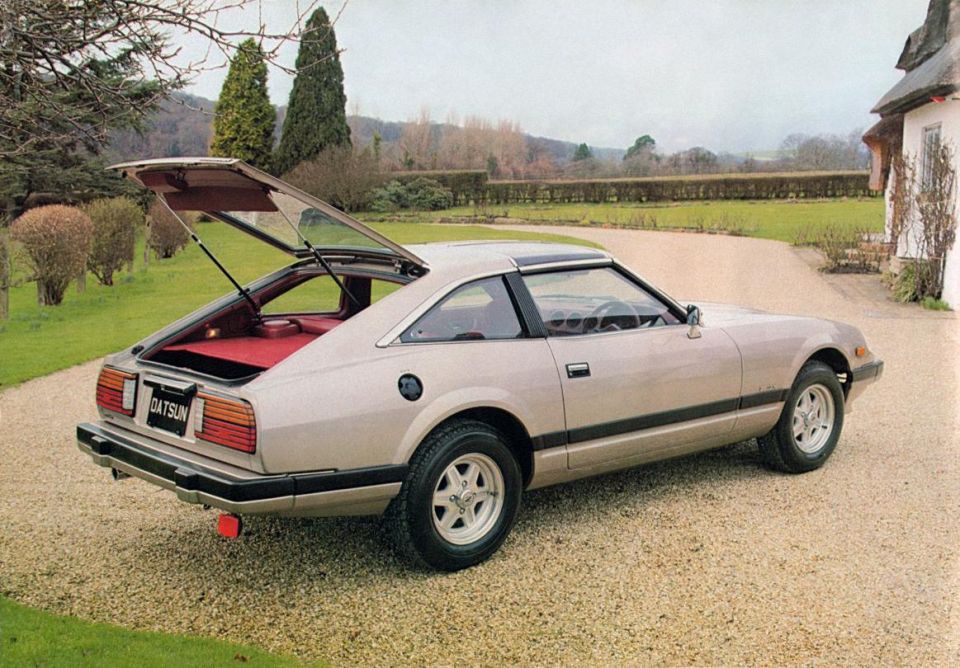

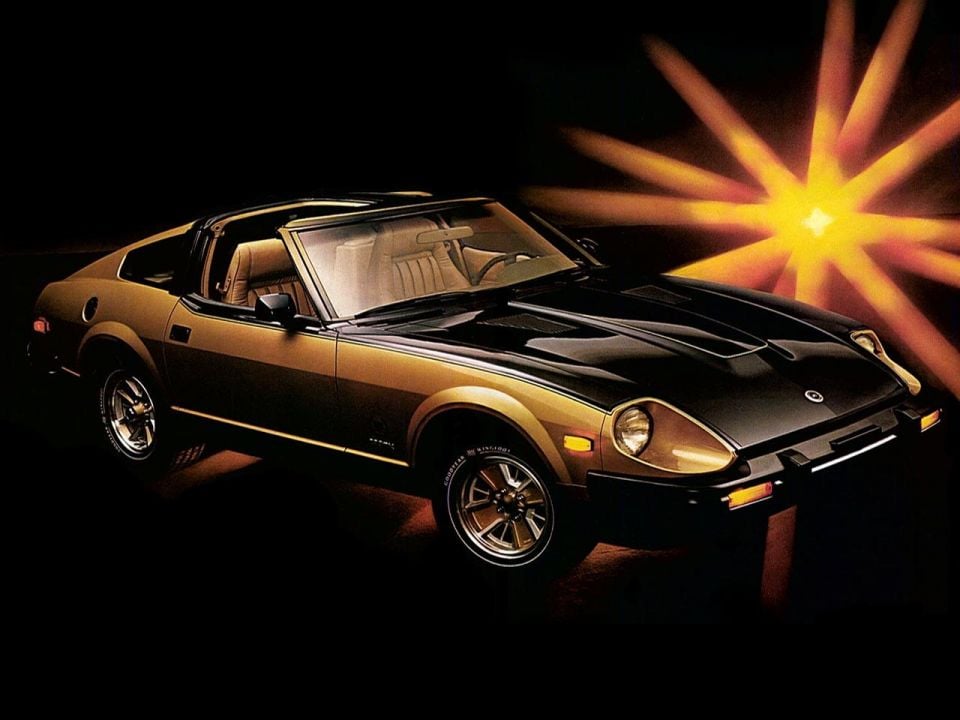

The 280ZX arguably completed the Z-Car’s transformation from lithe sports car to plush boulevardier. Blame the United States, the Z’s most important export market.

The American automakers were prioritising plushness and luxury accoutrements because performance was such a hard sell, especially in the wake of the first oil crisis, tough emissions standards and rising insurance premiums.

Nevertheless, there was still a market for sporty-looking coupes, however, as evinced by the resurgence of the Chevrolet Camaro and Pontiac Firebird. Datsun tapped into the zeitgeist with the new 280ZX and managed to boost Z-Car sales in this crucial market to their highest numbers yet.

The 280ZX was more powerful and aerodynamic than its predecessors, with a new fuel-injected 2.8-litre inline-six and a lower drag coefficient of 0.385, down from 0.467.

It was also bigger, though, measuring 280mm longer than the 260Z on a 20mm longer wheelbase in two-seater form. All Australian-market models, however, were the longer 2+2.

A turbocharged engine was available for the first time, though markets like Australia and Japan missed out. The Japanese market did, however, get naturally-aspirated and turbocharged 2.0-litre inline sixes, badged as the Fairlady 200Z.

If you remember the 280ZX for one thing, though, let it be this: perhaps the most epic TV commercial in automotive history. If the 280ZX didn’t already have a reputation as the car of choice for the unbuttoned shirt and gold chains crew, this TV spot sure gave it one. That’s quite a porn-stache.

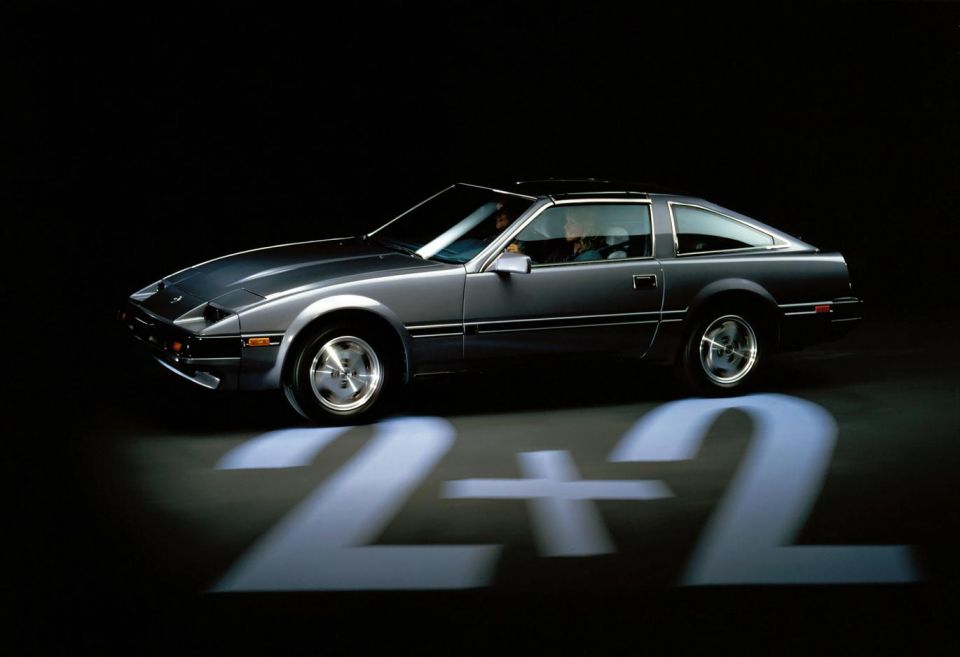

While its proportions and its tail lights looked similar to the 280ZX that preceded it, the 300ZX was very clearly a product of the 1980s and adopted the sharp angles and sheer sides expected of a sports coupe in the leg warmer era.

The new 300ZX nameplate was used for export models and was offered with a choice of naturally-aspirated and turbocharged versions of Nissan’s new single-overhead cam 3.0-litre V6 engine, the first production V6 out of Japan.

For the first time, the turbo model was offered here albeit after a delay of a couple of years, with both engines available in a single 2+2 body style with a targa roof. In other markets, a shorter-wheelbase two-seater continued to be offered, while electronically-adjustable dampers were newly available.

In its home market, the Fairlady Z offered various other engines. A turbocharged inline-six was still available, displacing 2.0 litres and sold in the 200ZR model.

This would be the last generation of Z-Car to offer an inline-six. Other forbidden fruit included a turbocharged 2.0-litre V6, used in the 200Z, 200ZS and 200ZG, and a naturally-aspirated double-overhead cam 3.0-litre V6 used in the 300ZR.

The 1986 300ZX Turbo introduced the first Australian-spec suspension tune for a Z-Car; past Z-Cars had used a “general export” tune that was somewhere between softer US and firmer European settings. Two years later, the Z31 was treated to a facelift that helped smooth out its styling.

The 300ZX was more aerodynamic than its predecessors, boasting a Cd of 0.31. Unfortunately, it was even heavier than the 280ZX that had already been criticised for its corpulence.

Though the later Aus-spec suspension tune helped tidy up its dynamics, the 300ZX – like its predecessor – was very much a grand tourer. Case in point: by the middle of this generation’s run, over 60 per cent of Australian-market 300ZXs had an automatic transmission.

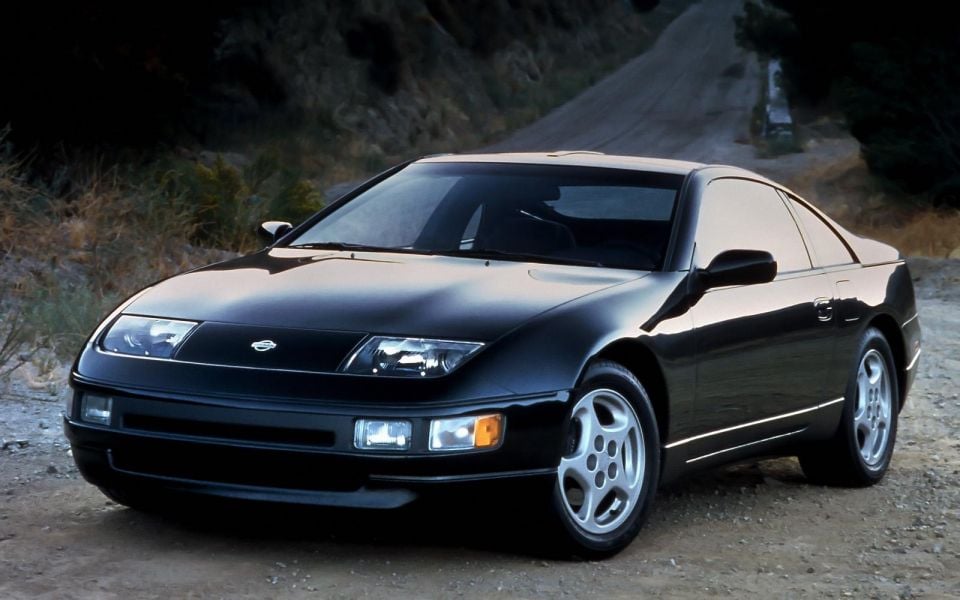

For the 1989 Z32, the first and thus far only Z-Car generation to retain the nameplate of its predecessor, Nissan dramatically slimmed down its JDM model range. Just two engines were offered: a naturally-aspirated 3.0-litre V6, now with double overhead cams and variable valve timing, and a new twin-turbocharged variant.

Surprise, surprise: Australia missed out on the latter. While the atmo V6’s outputs of 168kW of power and 271Nm of torque were nothing to sneeze at, the boosted V6 bumped those up to a heady 224kW and 384Nm. The 300ZX Turbo also offers Nissan’s trick new Super-HICAS four-wheel steering.

Once again, Australia only received the larger 2+2, which measured 85mm shorter than its predecessor, as well as 75mm wider, 40mm lower and with a 50mm longer wheelbase. Kerb weight was virtually unchanged.

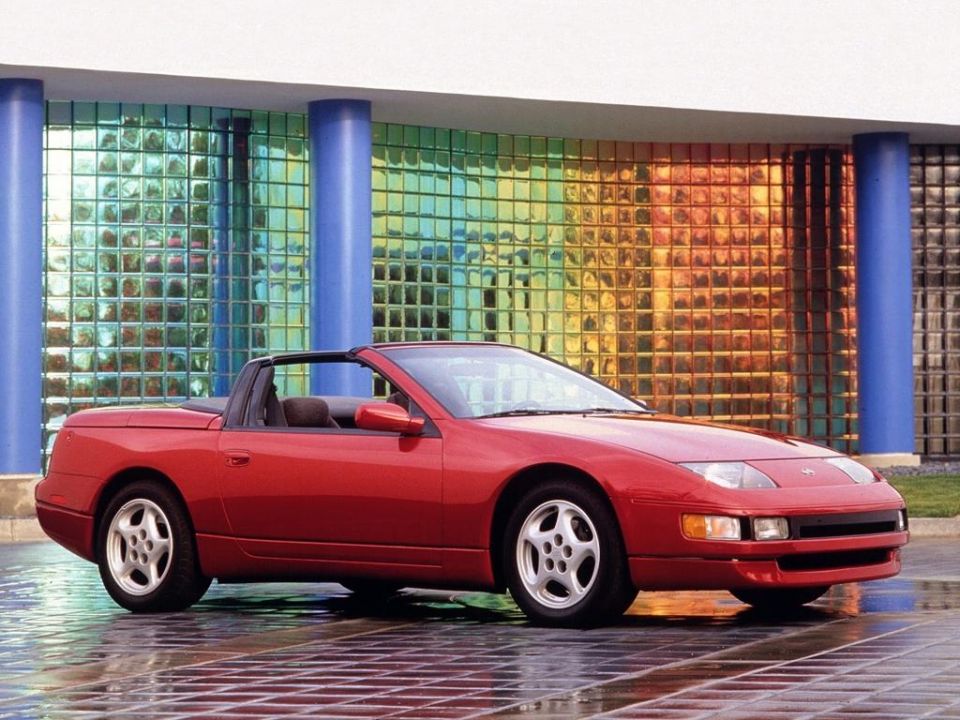

For 1992, North American buyers were able to purchase the first convertible Z-Car. The conversion was done by the American Sunroof Company, who had also lopped the top off other Japanese coupes like the Toyota Celica and Paseo, Mitsubishi 3000GT and Eclipse, and the Infiniti M30 (née Nissan Leopard).

The Z32 was met with immediate critical acclaim at its launch, with reviewers calling it a return to form for the Z-Car line after two generations of plush yet unexciting cruisers. The late 1980s and early 1990s was the golden age for Japanese sports coupes and this was one of the most impressive of the breed.

Unfortunately, the golden age was short-lived. An economic downturn in Japan forced automakers to cut costs and eliminate slower-selling models while a shift away from coupes in the critical US market plus an unfavourable exchange rate saw 300ZX sales decline from 39,290 units there in 1990 to just 4176 in 1995.

Nissan pulled the plug on the 300ZX both in North America and locally by 1996, though it continued to be offered in its home market until 2000.

The early 2000s wasn’t a good time to be a Japanese sports coupe. The Mitsubishi 3000GT and Toyota Supra died at the turn of the century, while even more affordable, long-running models like the Toyota Celica and Honda Integra wouldn’t survive beyond the end of the decade.

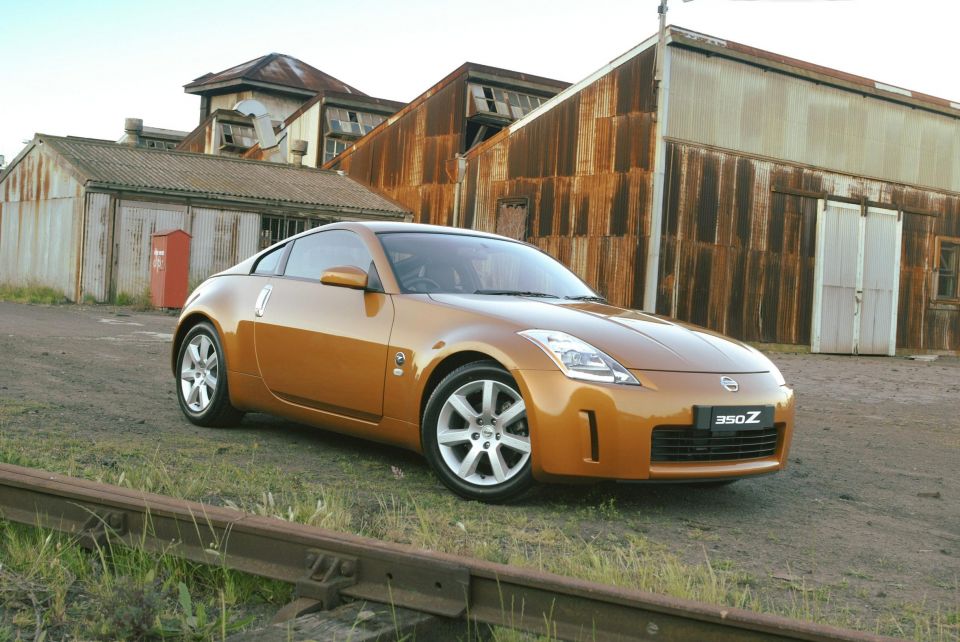

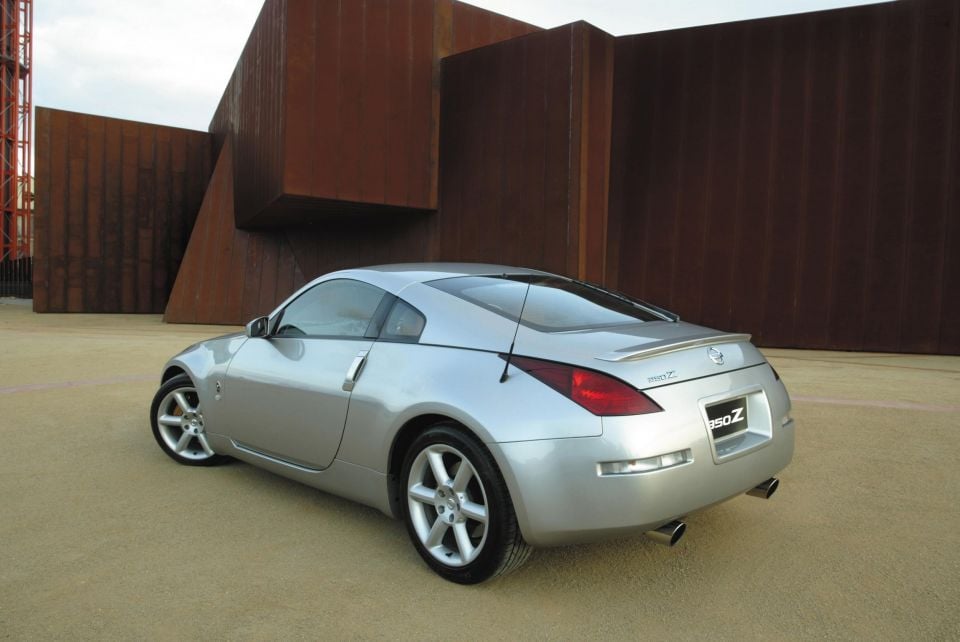

Nevertheless, Nissan resurrected the Z-Car. The 350Z was the first Z-Car since the 240Z to go without a longer-wheelbase, 2+2 body style.

If you wanted a more spacious coupe, Nissan had the new V35 Skyline (aka Infiniti G35) with which the 350Z shared its FM platform.

T-tops were also nixed in favour of the Z’s first factory convertible. In a break with the past, the “X” letter was ditched as the 350Z looked towards the more pure 240Z and 260Z for inspiration rather than the cushier 280ZX and Z31 300ZX.

The styling – from Nissan’s California design studio – wasn’t a retro throwback, however. It was even squatter and arguably more aggressive than the slippery Z32 300ZX, with an almost identical length to the two-seater Z32 but a 200mm longer wheelbase.

Three generations of turbocharged Z-Cars came to an end with the 350Z, which used a single, naturally-aspirated 3.5-litre V6 with 206kW of power and 363Nm of torque mated to either a six-speed manual or five-speed automatic transmission.

Its base price slid just under the $60,000 mark when it arrived locally at the end of 2002, putting it line-ball with the Holden Monaro CV8 and therefore undercutting less inspiring European fare like the Mercedes-Benz C200 Sports Coupe.

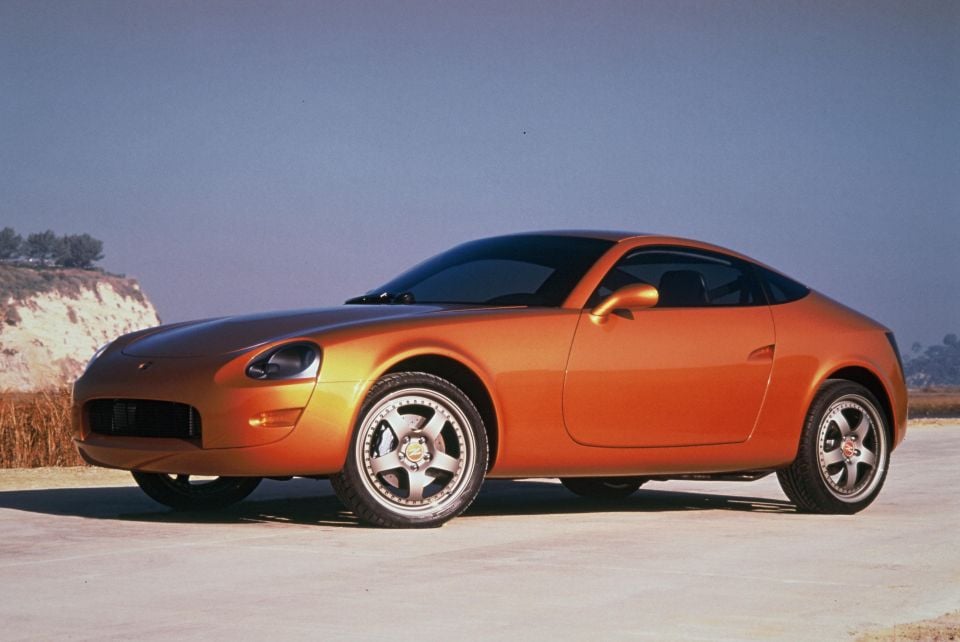

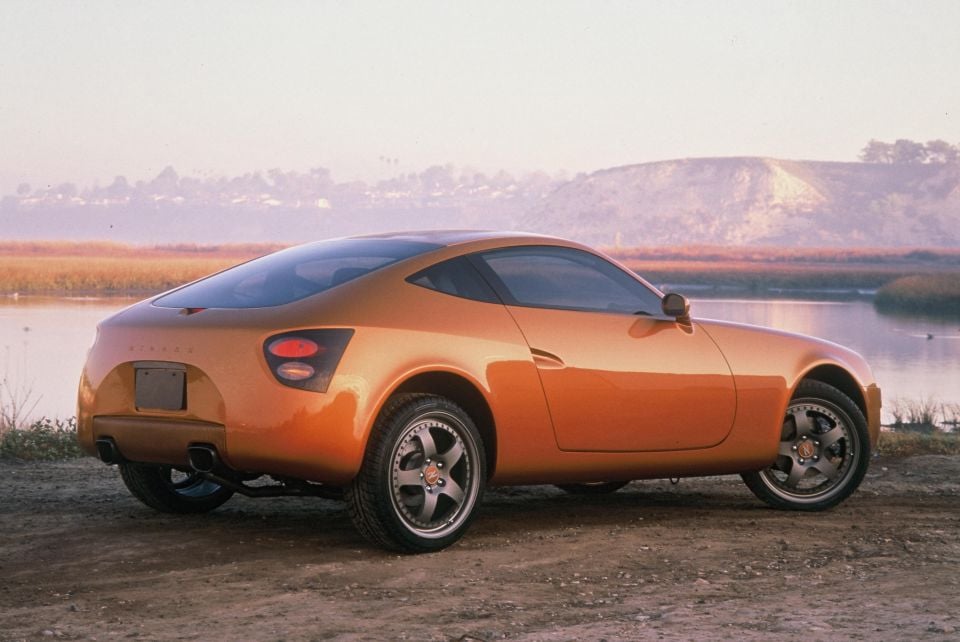

Fortunately, the 350Z was much more impressive than the 240Z concept presented at the 1999 Detroit motor show. Its styling was unresolved and, while the name was accurate and it was powered by a 2.4-litre engine again, it used a four-cylinder borrowed from the Altima. Unworthy.

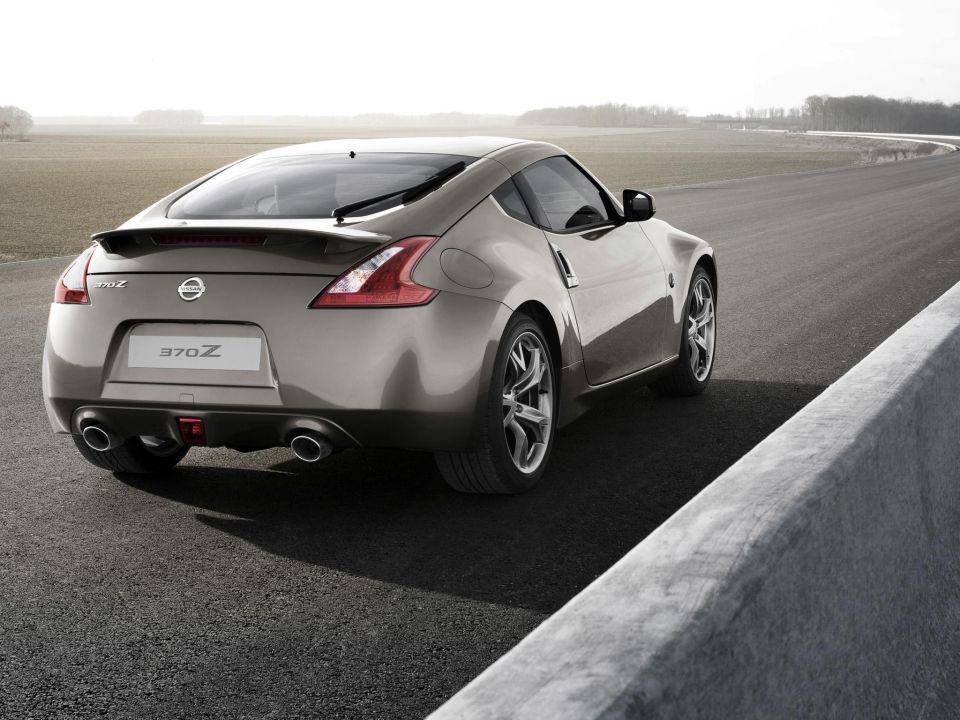

Benchmarked against the Porsche Cayman, the 370Z saw the Z-Car shrink once again – it rode a 100mm shorter wheelbase, though the front and rear tracks were 15mm and 55mm wider.

A larger 3.7-litre V6 powered the 370Z, with outputs up to 245kW and 363Nm; a seven-speed automatic replaced the five-speed unit, while the six-speed manual remained.

Styling was more aggressive than before and it’s aged fairly well externally, especially considering the 370Z has now been on sale for over a decade. Inside the cabin, it’s a different story – and yet 370Z sales haven’t fallen off a cliff.

Instead, it’s been a gradual decline in markets like the USA which, while no longer a goldmine for Nissan as it was in the era of the 280ZX, remains an important market.

The US market is also likely one of the key reasons the next-generation Z-Car is even being made and why a manual is being offered – Americans may not like manual transmissions in mainstream cars but they’ll still buy ‘em in sports cars.

What’s your favourite generation of Z-Car? Let us know in the comments!

Where expert car reviews meet expert car buying – CarExpert gives you trusted advice, personalised service and real savings on your next new car.

William Stopford is an automotive journalist based in Brisbane, Australia. William is a Business/Journalism graduate from the Queensland University of Technology who loves to travel, briefly lived in the US, and has a particular interest in the American car industry.

James Wong

6 Days Ago

Max Davies

5 Days Ago

Josh Nevett

3 Days Ago

Max Davies

3 Days Ago

Max Davies

2 Days Ago

Derek Fung

2 Days Ago