James Wong

2026 Porsche Macan review: Long-term introduction

6 Hours Ago

We all remember those heady days in the 2000s when taxis used LPG and dual fuel vehicles were common. But how did they work and what caused their demise?

Contributor

Contributor

Petrol, diesel, electric and hydrogen. These four sources of power are all well known today – and the majority of cars on the road are powered by one (or a combination of) these sources.

Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG) was very popular in the past, but has recently declined in usage and popularity. Let’s have a look why.

The LPG used in cars is very similar to the fuel in the gas cylinders you use to power your barbecue in the summer. In Australia, the LPG used to power your BBQ is propane gas, whilst the LPG used to power your car may also be known as ‘autogas’ and consists of a blend of propane and butane.

LPG is a fossil fuel, and so shares certain characteristics with petrol and diesel. In turn, this also means the fundamental production process for LPG has some commonalities.

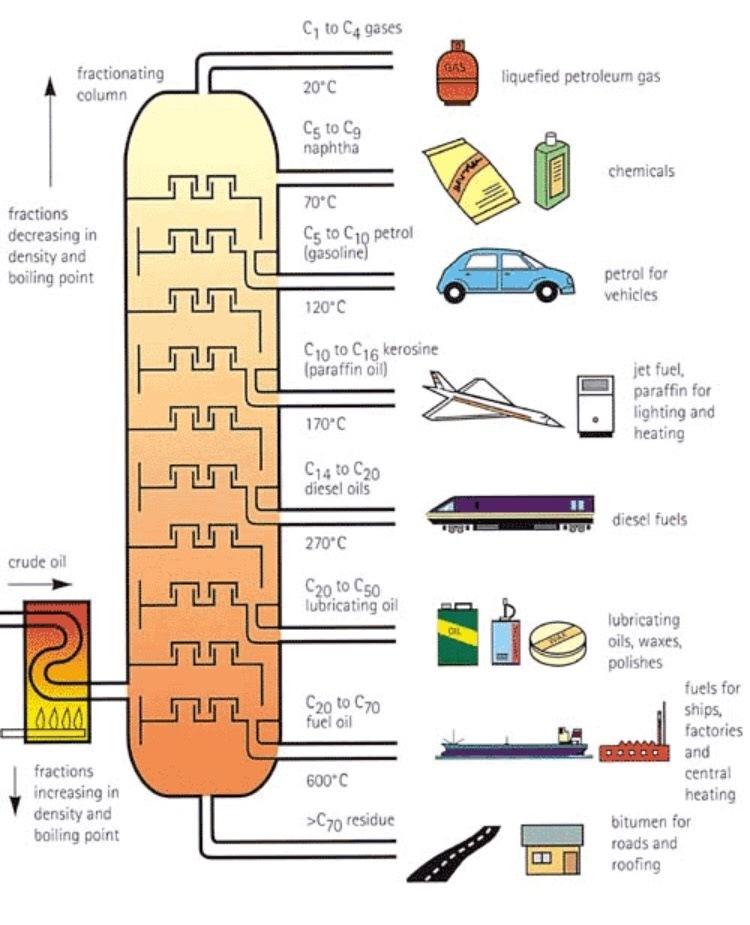

There are two primary sources for LPG – crude oil (also the source of petrol and diesel) and raw natural gas.

LPG sourced from raw natural gas goes through what’s known as the NGL (Natural Gas Liquids) fractionation process where it’s stripped from the natural gas, whilst LPG sourced from crude oil goes through a fractional distillation process, similar to the production of petrol and diesel.

The end product is identical, but the majority of Australian LPG is sourced from raw natural gas.

The detailed production process is beyond the scope of this article but once refined, LPG can then be further separated into propane, butane, and isobutane, or contain a combination of these three hydrocarbons.

That distinctive smell you notice whenever you fill up an LPG car or open a gas tank cylinder to light up the barbecue? That’s known as the safety odourant, and is a chemical called ethyl mercaptan and is deliberately added to LPG after it has been refined. Otherwise it would remain colourless and odourless, and a leak would pass unnoticed.

The ‘L’ in LPG comes about as the gas becomes a liquid under pressure, in order for it to be stored and transported more easily.

The similarities between LPG and its petrol and diesel counterparts mean that an LPG car shares the same internal-combustion basics as a regular petrol or diesel.

This is also the reason many Holden Commodores, Ford Falcons and other petrol cars back in the day were able to have an aftermarket conversion to be a ‘dual-fuel’ vehicle at a reasonable price.

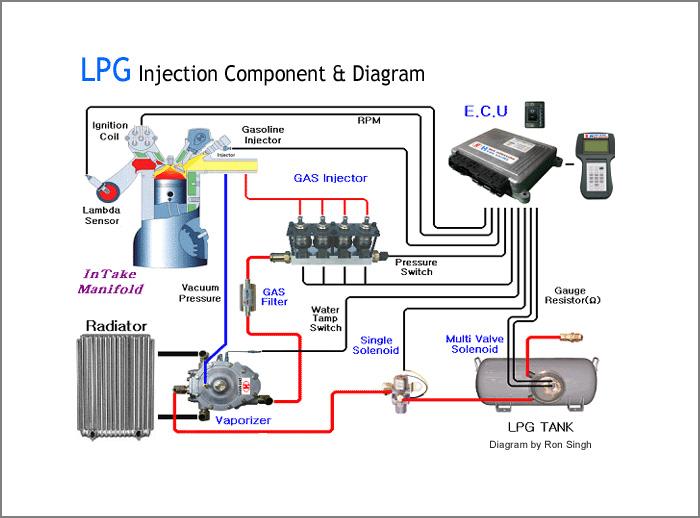

The dual-fuel conversions add a separate fuelling system to the car, including dedicated LPG injectors, piping, and a switch to allow the driver to choose between petrol and LPG, with the LPG tank taking up space in the boot or under the car.

However, aftermarket conversions are not the only way to own an LPG powered car, with some vehicles (see below) previously being offered direct from the factory with LPG variants. Regardless of how the car has been made to run on LPG, there are four key intake systems.

LPGConverter and Mixer systems are the oldest type of LPG fuel system. These use a converter that transforms the liquid LPG into a vapour, that is subsequently mixed with air before being transferred into the engine’s intake manifold – the part of the engine that transfers the air/fuel mixture into the cylinders.

Vapour Phase Injection(VPI) is similar, except the gas leaves the converter in a pressurised form enabling it to be injected into the intake manifold. This is a more efficient system as the injector can be electronically controlled, and thereby improve the metering of fuel as compared to a mechanical converter and mixer system.

Rather than converting LPG into a vapour, liquid injection systems inject liquefied LPG directly into the engine.

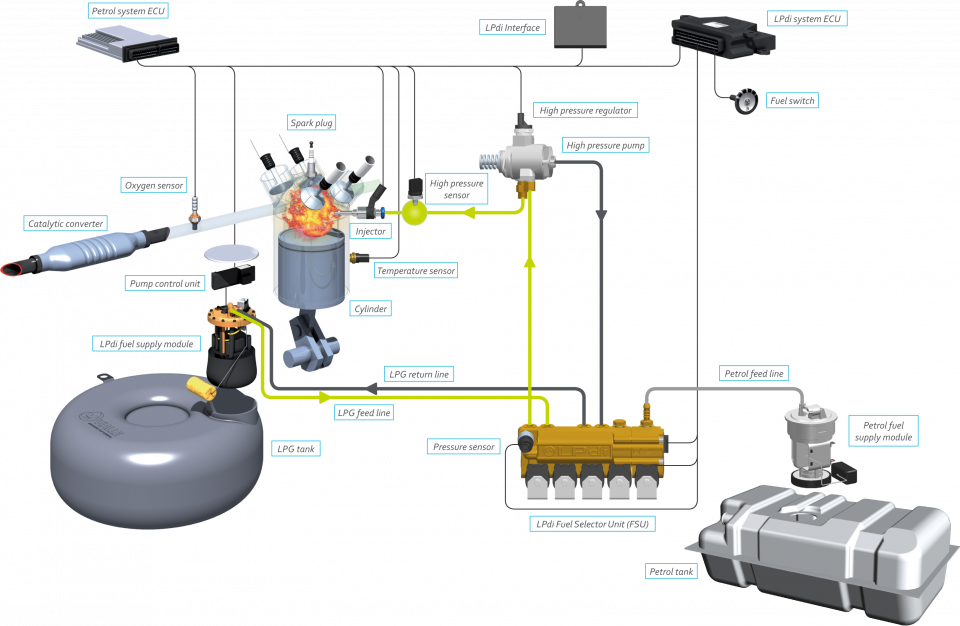

There are two liquid injection systems used. These are Liquid Phase Injection(LPI) and Liquid Phase Direct Injection (LPDI), with the primary difference being that LPI systems inject liquid LPG into the intake manifold, whilst the LPDI alternative is more advanced and injects the LPG directly into the combustion chamber (cylinder).

The primary advantage of LPG is its lower price compared to petrol. As of writing, LPG prices have a discount of approximately 20c per litre when compared to standard E10 unleaded petrol.

The lower cost of filling up is the primary reason why the fuel was so popular with taxis – any initial conversion costs (which can typically range from $3000-$5000) were more than offset by the lower running cost over the lifetime of a car. LPG conversions make more sense if you drive a lot.

However, the price gap between LPG and unleaded petrol is smaller than it used to be, and the fuel has been losing popularity as service stations offering the option have become increasingly scarce, especially in regional areas. This is also compounded by the higher fuel consumption of LPG systems as compared to petrol, negating some of the cost savings.

There are also practical and driveability disadvantages that accompany LPG systems – with reduced boot space and/or ground clearance for SUVs (if the LPG tank is mounted under the car), and usually a loss in power and torque compared to the petrol alternative.

Emissions wise, however LPG is a more environmentally-friendly option than petrol or diesel, producing less CO2, ozone, and nitrogen oxides (NOX) than either petrol or diesel.

The aftermarket has options to convert many popular vehicles to LPG. Indeed, LPG systems are available for the Toyota Camry Hybrid in what is marketed as an innovative ‘tri-fuel system’.

There are no new cars available for sale in Australia with a factory fitted LPG system, with the most recent options being the locally-built Holden Commodore and Ford Falcon.

When they were produced, Holden and Ford decided to take different approaches with their LPG systems.

Holden used a vapour injection system that reduced LPG fuel consumption, but also caused a corresponding decrease in power, whilst Ford’s ‘EcoLPI’ system went with the more sophisticated LPDI direct injection route, offering similar power to its petrol counterpart but higher fuel consumption.

But why the general demise in LPG vehicles? The end of local manufacturing (no imported cars recently sold in Australia have been offered with a factory LPG option) plays a part.

However, perhaps a more significant reason was the end of government subsidies. In 2006, the Howard government introduced a $2,000 rebate to convert cars to LPG, which offset a large part of the aftermarket conversion cost, but this was scrapped in 2014.

Additionally, 2011 saw the introduction of an LPG fuel excise, thereby reducing some of the cost benefits of filling up with LPG.

Today, the running cost and environmental advantages offered by LPG cars have been supplanted by hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and electric vehicles.

James Wong

6 Hours Ago

Toby Hagon

13 Hours Ago

William Stopford

14 Hours Ago

William Stopford

14 Hours Ago

James Wong

16 Hours Ago

Damion Smy

18 Hours Ago