Ben Zachariah

2026 LDV Deliver 9 campervan released with sharp pricing

19 Hours Ago

News Editor

Over the years, Nissan’s product planning has often been as scattershot as Holden’s was. The Japanese brand’s history is littered with nameplates that lasted only a single generation, from the Almera to the Serena.

Likewise, even long-running Nissan model lines have featured short-lived variants – witness the Navara and Pathfinder 550 models with their 170kW/550Nm turbo-diesel V6s, or the R30 Skyline, the only Skyline to offer a hatchback body style.

Nissan is currently in the midst of revitalising its lineup, launching new Qashqai, X-Trail and Pathfinder SUVs plus a new Z this year. Therefore, we thought we’d take a look back at the brand’s colourful history in Australia, including vehicles from before the Nissan name was even being used here.

MORE: 10 Chryslers you may have forgotten about MORE: 10 Fords you may have forgotten about MORE: 10 Holdens you may have forgotten about

The Datsun 200B was a “180B with 20 more mistakes”, or so the old saying goes. And yet, the 200B generally sold better than the 180B and remained one of Australia’s popular mid-sizers.

The 200B’s success in Australia stands in contrast with its sales performance in Japan, where it was a commercial failure. That explains why the 810-series Bluebird, as it was known there, was only in production there for just over three years.

Though it was available with a longer nose and a straight-six engine in markets like Japan and the US, the 200B was introduced late in 1977 with a 2.0-litre four-cylinder producing 70kW and 152Nm and mated with either a four-speed manual or three-speed automatic.

Initially, the 200B range was imported from Japan and, unusually for this segment in Australia but like its 180B predecessor, it was fitted in sedan and coupe variants with an independent rear suspension; the wagon had a live rear axle with leaf springs. But despite the presence of IRS, the days of the dynamic 1600 (aka 510) were a fuzzy memory at this point.

Contemporary reviews found the 200B thoroughly underwhelming, from its noisy engine to its vague recirculating ball steering (common among Japanese mid-sizers), and its indifferent handling.

Styling was still typically heavy-handed 1970s Datsun. Though the 180B’s bulges and coke-bottle contours were toned down, it looked a bit flabby, particularly against the likes of the crisper Sigma and Ford TE Cortina.

The SSS coupe was no great beauty, either, featuring an unusual roof line with a separate rear window. It was rather reminiscent of the 1974-76 Ford Gran Torino coupe – this was a time when the Japanese brands were very much inspired by the American automakers, even as American designs traded their handsome lines from the 1960s for pretentious grilles, opera windows and padded vinyl roofs.

The lone two-door upgraded from a four-speed to a five-speed manual, with a three-speed automatic still optional; the five-speed was criticised for confusingly having reverse where first gear would be in most cars. Outputs were unchanged, though there were unique wheels and additional convenience items.

While 200B sales were up over the popular 180B, the entire segment had been buoyed by a significant shift – particularly by fleet operators – towards mid-sized cars in the wake of the first oil crisis. And the 200B couldn’t enjoy the exalted status of Australia’s most popular mid-sizer, with that honour bestowed upon the Chrysler (later Mitsubishi) Sigma, introduced in 1977. By 1980, the Sigma had a 28 per cent share of the segment and the 200B was behind at 16 per cent.

In 1978, as part of a shift to local production, all sedan models switched to a locally-built Borg-Warner live rear axle with coil springs to reach an 85 per cent local content target; the wagons and the imported SSS coupe stuck with their existing rear suspension set-ups.

While switching from IRS to a live rear axle sounds like a retrograde step, contemporary reviews found the 200B to be improved from the change, likely as it involved more extensive local engineering.

The SSS coupe proved to be short-lived, discontinued during 1979. A year earlier, a sporty-looking SX sedan was introduced. This was developed locally, not at Datsun’s Japanese HQ, and featured a unique front end with a racy air dam, plus alloy wheels, pinstripes, and lurid striped cloth upholstery, though it lacked the SSS’s five-speed manual. It also featured stiffer springs than the rest of the sedan range, delivering a firmer ride.

The SX’s new front end presaged a 1980 facelift where the entire 200B range ditched its buck-toothed front fascia and received a raft of enhancements, including revised suspension, reduced noise and vibration, a new variable-ratio steering box, and new seats. The 200B had by now arguably become the vehicle it should have been all along.

Though it was short-lived in Japan, the 200B lingered on here until 1981 when the new Bluebird was finally introduced, around two years after it appeared on its home market. There’d be no coupe like in Japan, although the ostensibly sporty TR-X variant would be a successor to the 200B SX.

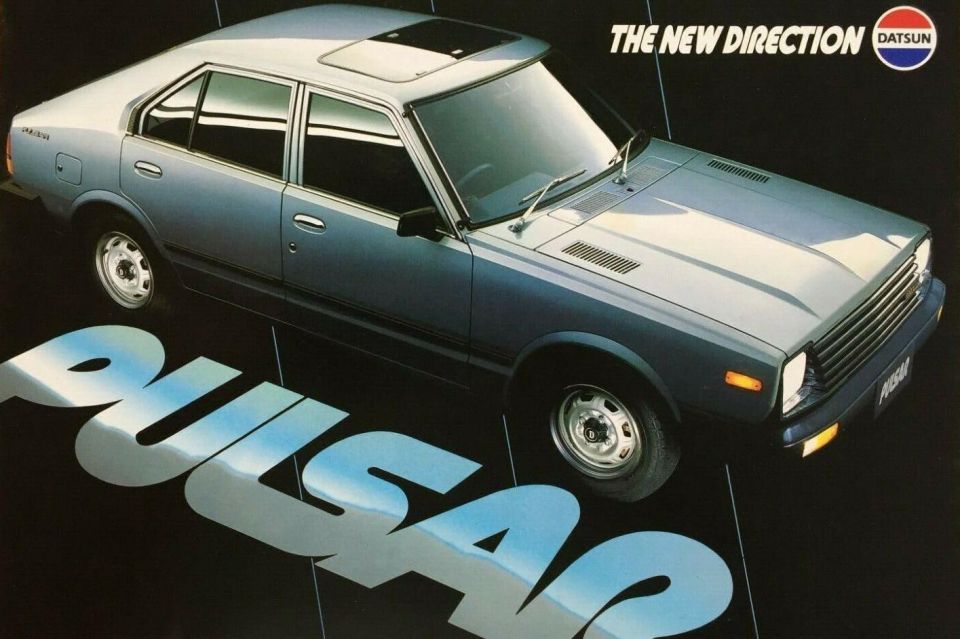

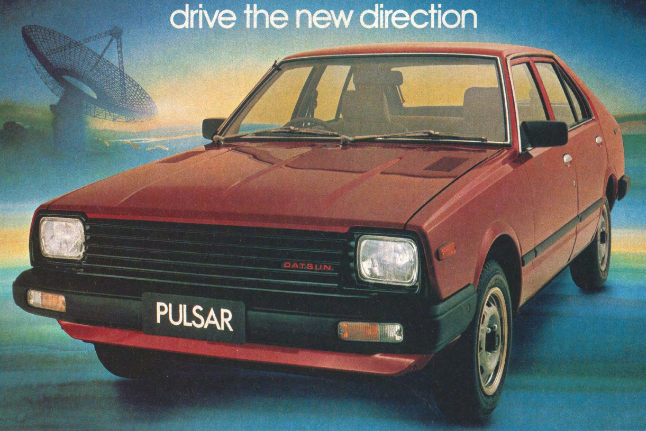

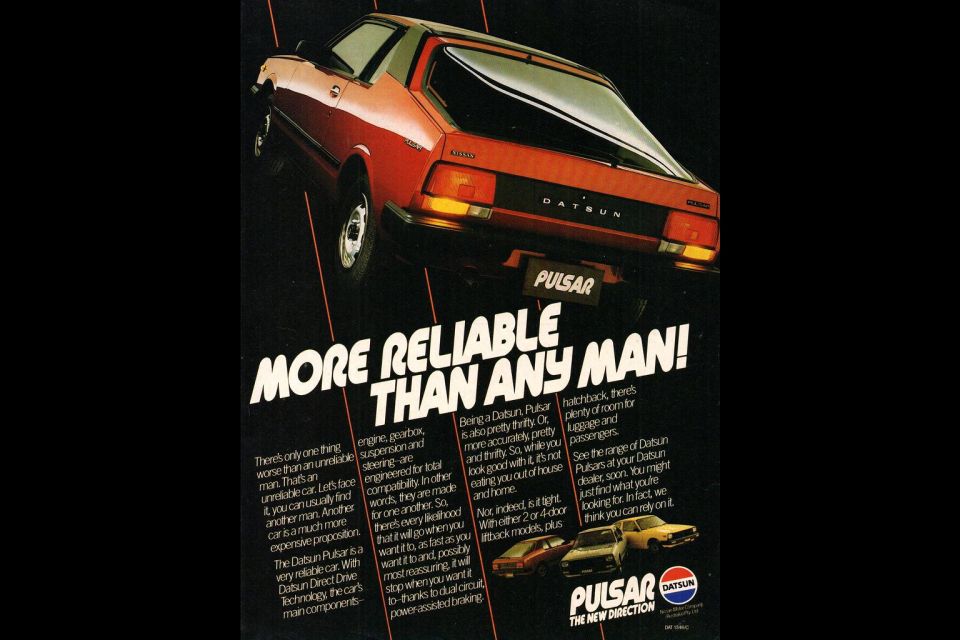

Before the Nissan Pulsar was built locally and became one of Australia’s best-selling small cars, there was the short-lived, imported Datsun Pulsar. It’s perhaps most noteworthy for its rare coupe variant, sold for only one year.

The late 1970s and early 1980s was a transition period for Datsun’s small car range. The 120Y may have been unusual-looking and dynamically so-so and yet it was popular. What would assume its mantle?

First came the Stanza sedan in 1978, a locally-built version of a vehicle known in Japan as the Violet and which dusted off the vaunted Datsun 510 nameplate in some markets. It slotted just below the 200B, with which it shared various components, and sat above the imported Sunny sedan, coupe and wagon, launched in 1979 and the next-generation version of the 120Y. Finally, the imported Pulsar hatchback arrived in 1980, two years after its Japanese launch.

It got off to a slow start, but Nissan saw which way the market was heading. It had offered a small, front-wheel drive hatchback since the 1970 Cherry, but had never sold these fruity Nissans here.

It had also persisted with rear-wheel drive for the larger 1200/120Y/Sunny but the more space-efficient front-wheel drive format had been rapidly proliferating through this segment, and the B310 generation of Sunny would be the last with rear-wheel drive.

Production of the B310 Sunny ended in 1981, with the B11 Sunny/Sentra switching to front-wheel drive. Likewise, the larger Stanza would switch to front-wheel drive in 1981 and the Bluebird in 1983, but neither would be sold here. Nissan Australia persisted with its rear-wheel drive Bluebird, but established the Pulsar as its entry-level front-wheel drive model.

The 1980 N10 generation was essentially an imported stopgap model until the N12 hatchback and sedan would enter local production in 1983, and went up against new front-wheel drive models like the Ford Laser, Mazda 323 and Mitsubishi Colt. Datsun even referred to it as “the forerunner of a new breed of car designed for total energy efficiency” in its advertising.

The Pulsar had a base price higher than that of the Sunny, Stanza and even the 200B (the latter by $100), but it did have a decent list of standard kit for a small car in 1980 with tinted windows, cloth upholstery and remote fuel door and hatch releases.

It used a dated pushrod 59.6kW/112Nm 1.4-litre four-cylinder from the Sunny wagon when many rivals were using overhead-cam engines. However, it was mated exclusively with a five-speed manual transmission when some rivals were still using four-speeds. Also noteworthy was the Pulsar’s use of four-wheel independent suspension.

The packaging benefits of front-wheel drive didn’t seem to translate to the long-nosed Pulsar, as Datsun had reportedly designed it so it could be reengineered for rear-wheel drive if necessary. This never came to be. Critics at the time noted back-seat accommodations were none too stately, while dynamically the Pulsar was considered merely average.

Styling would get crisper with the N12, but even the N10 represented a shift away from the unusual, organic design language of 1970s Datsuns. More fussy was the coupe body style, introduced for 1982 as part of a “reboot” for the Pulsar line and featuring a large rear window and a wraparound C-pillar treatment.

Surprisingly for a vehicle at the end of its lifecycle, the rebooted Pulsar received revised suspension and steering and two new overhead-cam four-cylinder engines: a 1.3-litre with 44kW and 96Nm, mated with a four-speed manual, and a 51.4kW/115Nm 1.5-litre with either a five-speed manual or three-speed automatic.

There were now base, TL and TS trims, with the new coupe offered exclusively in the highest level of trim. A three-door hatch body style also joined the range.

For 1981, Nissan projected 22,000 sales across the Stanza and Sunny lines, plus 6000 of the Pulsar. But in 1982, Datsun sold just 14,662 vehicles across the Stanza and Pulsar lines, which also included leftover Sunny stock. In contrast, Toyota sold 22,916 Corollas and Ford sold 40,069 Lasers, though in the Pulsar’s defence it was limited by import quotas.

The N10 Pulsar had, however, helped introduce the concept of a small, front-wheel drive Nissan to Australian buyers and established the Pulsar nameplate. Its N12 successor would prove much more popular.

A year after the Pulsar was redesigned, a new variant joined the range but it’s now an almost completely forgotten footnote.

Though no wagon was available in the Pulsar range, September 1983 brought a Pulsar Van to replace the defunct Datsun Sunny Van. It was claimed to be the first front-wheel drive half-tonne van sold in Australia, and boasted a payload of 540kg while weighing just 840kg. Owing to its load-lugging pretensions, the rear suspension featured a beam axle and leaf springs.

It wasn’t exactly a Pulsar. Instead, this was a rebadged AD Van, derived from the B11 Sunny/Sentra sold in markets like Japan, which was in turn mechanically related to the Pulsar sold here.

It was available in just one variant, which featured headlining throughout the vehicle, as well as carpeted floors and cloth upholstery. Power came from a 44kW/100Nm 1.3-litre four-cylinder engine, mated to a four-speed manual transmission.

At the time, there were a handful of small, car-based vans on the market. These included the Mazda 323, Holden Gemini, and Toyota Corolla, all of which were rear-wheel drive. Nissan’s promotional material touted it as having the largest load area in its class, 11 per cent larger than that of the Mazda 323 and with 25 per cent higher payload.

Nissan evidently wasn’t able to sell the benefits of the Pulsar Van to a wide audience, as it lasted just two years on the local market.

Nissan shocked many with its unconventional, boxy Prairie in 1983, and it clearly was too far outside the mainstream to succeed in Australia.

Launched in Japan in 1982 and arriving here the following year, it was quickly followed by the conceptually similar Mitsubishi Nimbus in 1984. Both featured three rows of seats, as well as four-cylinder engines. Both of these models shared mechanicals with cars in their brand’s line-ups, instead of being based on delivery vans, though Mitsubishi (Starwagon) and Nissan (Nomad, Urvan) would also offer such vehicles in Australia.

Mitsubishi had actually been first with a design study (the 1979 Super Space Wagon concept) but Nissan beat it to market. But while the more conventional-looking Nimbus would go on to survive another three generations in Australia, the Prairie would clock out in 1985.

Whether you called them people movers, MPVs or minivans, this format was in its infancy in the early 1980s. Renault and Chrysler had both staked a claim to inventing the modern people mover – the former with the 1984 Renault Espace, the latter with the 1984 Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager, none of which were sold here – but Mitsubishi and Nissan had beat them to market with their smaller models.

Besides, they were all late to the game if you count the Fiat 600 Multipla or the even earlier Stout Scarab as the first people mover…

The Prairie’s design appeared to pay homage to the 1979 Lancia Megagamma concept by Italdesign, though it was even more boxy and upright. There were dual rear sliding doors, unlike the Nimbus and Espace, and unusually there was no B-pillar. Nissan claimed it ensured rigidity by strengthening the structure around the side openings and using thicker steel.

Under its unorthodox skin, it shared much with Nissan’s global small cars like the Pulsar and Sentra/Sunny. It rode a longer 2510mm wheelbase than the Pulsar, but despite seating seven it was only 130mm longer than a Pulsar sedan. Where it was most different dimensionally was in height, with its boxy, tallboy styling making it around 200mm taller than a comparable sedan.

The only engine offered here was a naturally-aspirated 1.5-litre four-cylinder, shared with the Pulsar, which produced 51kW of power and 115Nm of torque. That engine was mated exclusively with a five-speed manual transmission.

Why Nissan chose to only offer this powertrain here is unclear. Not only were there larger, more powerful 1.8-litre and 2.0-litre engines offered in other markets, the Prairie could also be equipped with an automatic transmission overseas and even four-wheel drive.

The Nimbus may have been around $1000 more expensive than the Prairie at first, but it offered the option of an automatic transmission and was more powerful (70kW/140Nm), if around 70kg heavier at 1065kg.

The Mitsubishi was also 195mm longer, better proportioned and therefore easier on the eyes, even if it did lack the Prairie’s sliding doors and absent B-pillar in favour of conventionally-hinged rear doors.

The Prairie finished its run early in Australia, with the facelifted 1985 model not making the trip here. And sadly, the second-generation model, which featured more aesthetically pleasing styling in the vein of the Renault Espace, was never offered here. It was withdrawn from the US market, where it was sold as the Axxess, after a single model year, and proved to be the last widely exported Prairie generation.

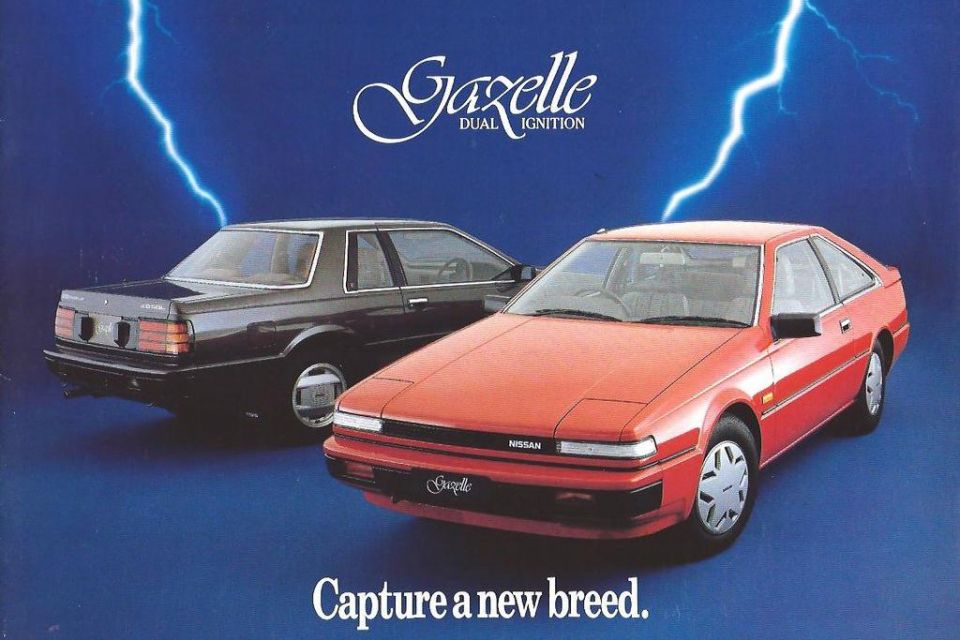

This Gazelle wasn’t mauled to death by a lion on the African savannah, but it was annihilated by the Toyota Celica on the Australian new car market.

Nissan Australia was asleep at the switch when it decided to finally bring the Silvia to Australia, a sporty rear-wheel drive coupe which by its third generation – called the S12 – was also sold in Japan under the Gazelle nameplate. The shapely notchback and hatchback were introduced here in 1984, with the kind of crisp, angular styling so very much in vogue.

While there were plenty of new car buyers who merely wanted the sporty looks of a coupe but didn’t necessarily care what was underneath, the Gazelle was imported here lacking even the option of the turbocharged four-cylinder engine available in Japan and the US. A V6 model was later offered in the US but it also didn’t make the trip.

That left a fuel-injected, naturally-aspirated 2.0-litre four-cylinder engine, producing 78kW of power and 160Nm of torque and mated with either a five-speed manual or four-speed overdrive automatic. This was the same CA20E engine later used in the Series III Bluebird update and its Pintara replacement, so it was nothing inspiring.

Australian-spec Gazelles came only with a live rear axle, too, despite the availability of independent rear suspension in other markets.

Let’s not forget, however, that the contemporary rear-wheel drive Toyota Celica was hardly the most dynamic coupe itself. That would change late in 1985 with the launch of the fourth-generation Celica, the first with front-wheel drive. The new Celica was widely regarded as being vastly superior to its predecessor dynamically and was an immediate hit.

The Gazelle, meanwhile, was criticised for its soft suspension tune, unrefined engine, twitchy handling and lifeless steering. It wasn’t even regarded as being on the same level dynamically as the carbureted, 1981-vintage third-generation Celica.

For some reason, Nissan positioned the Gazelle notchback as the more premium of the two body styles. It came standard with power windows, antenna and mirrors, alloy wheels, two additional speakers (for a total of six) and cruise control. It also offered more options, including a power sunroof (manual only in the hatch) and power steering.

Why Nissan chose to do this is unclear, especially when you consider the Toyota Celica was more popular as a hatchback than a notchback.

For 1986, the local-spec Gazelle received a series of mechanical revisions. Chief among these was the belated introduction of independent rear suspension, with semi-trailing arms, coil springs and an anti-roll bar. Rear disc brakes were also made standard, while gear ratios were revised for quicker acceleration and a new exhaust system was installed.

Not that acceleration got all that quicker, as we continued to miss out on more powerful engine options offered overseas. At least you could finally get power steering in the hatchback, and handling had been improved. It was pricier than before, but had a lower base price than the Celica.

The notchback was axed after 1986, leaving a single hatchback variant to soldier on until the line was axed in 1988. Nissan never officially sold its S13 Silvia/180SX successor here, and yet they’re plentiful and highly sought after. The Gazelle, in contrast, has disappeared into obscurity.

In the next instalment, we’ll look at five more Nissans you may have forgotten about.

Being a top 10 list, we’ll always have to leave some vehicles on the cutting room floor. Here are just a few honourable mentions:

MORE: 10 Chryslers you may have forgotten about MORE: 10 Fords you may have forgotten about MORE: 10 Holdens you may have forgotten about

Where expert car reviews meet expert car buying – CarExpert gives you trusted advice, personalised service and real savings on your next new car.

William Stopford is an automotive journalist with a passion for mainstream cars, automotive history and overseas auto markets.

Ben Zachariah

19 Hours Ago

William Stopford

21 Hours Ago

Derek Fung

21 Hours Ago

Alborz Fallah

21 Hours Ago

William Stopford

1 Day Ago

Ben Zachariah

1 Day Ago