In April 2025, Australian motorists will lose the ability to save substantial sums of money when leasing a plug-in hybrid vehicle (PHEV). This is because the EV Fringe Benefits Tax (FBT) exemption for novated leased vehicles is ending for PHEVs.

This isn’t a good outcome for anyone who wants to save money leasing a new PHEV and save money on fuel compared to a plain petrol or diesel passenger car, SUV or ute. It’s also not in line with the purpose of the legislation, which was incentivising cleaner cars that could emit less CO2.

Read on to find out why the government is dropping PHEVs from the novated lease incentive scheme and why this is the wrong time to remove PHEV incentives. First though, a brief backgrounder on PHEVs and the novated lease FBT exemption.

What is a PHEV?

PHEVs are a vehicle with both a combustion engine and a battery and electric motor(s), but unlike regular hybrids such as the Toyota RAV4, they have a much larger battery that allows them to run for many kilometres on electricity alone.

100s of new car deals are available through CarExpert right now. Get the experts on your side and score a great deal. Browse now.

Some models can get close to 100km of electric-only range – meaning for many people their daily commute can be done entirely on electric power.

The other defining feature of a PHEV is that it can be plugged in to a powerpoint or wall charger to recharge the battery.

What is the FBT exemption?

EVs and PHEVs are exempt from the FBT if they cost less than the Luxury Car Tax (LCT) threshold for fuel-efficient vehicles, currently sitting at $91,387.

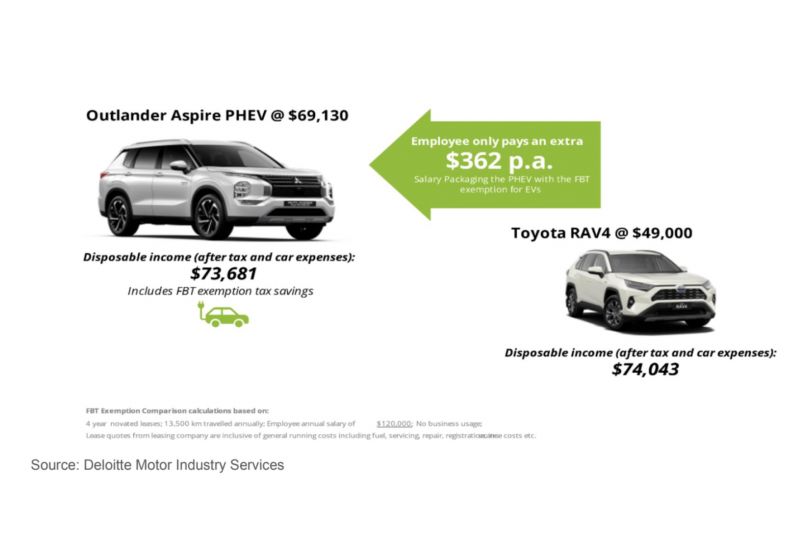

The FBT exemption for EVs on a novated lease means you could drive a considerably dearer EV for the same cost as a much cheaper petrol car.

To quote from the National Automotive Leasing and Salary Packaging Association (NALSPA), “Using pre-tax salary deductions, workers can reduce their taxable income, avoid GST on vehicle purchases and running costs, and benefit from a stable, predictable payment structure.”

The Australian Financial Review even lists it as a legitimate tax minimisation practice.

NALSPA CEO Rohan Martin provides a real-world example with a popular Tesla:

“Removing fringe benefits tax on a $50,000 low or zero-emissions car can save an employee around $4,700 annually,” he said.

“The exemption makes owning and driving a Tesla Model Y, which costs $64,000 drive away, cheaper than a $40,000 petrol-powered Mazda CX-5. Additionally, drivers save further on running costs by avoiding fluctuating fuel prices.”

Note that since we discussed this with Mr Martin, a Model Y is now even cheaper at between $58,715 and $62,553 drive-away, depending on your state and territory.

Why Is the PHEV FBT exemption going?

In one word – politics. The Government did not actually want this scenario to occur. The looming April 1 end-date for PHEVs EV FBT exemption came about as a compromise to get the novated leasing FBT legislation through the parliament to become law.

With no Liberal/National votes, the government required crossbench support. The final outcome of the negotiations was PHEV vehicles would be classified as EVs from the date the legislation commenced on July 1, 2022, but only until April 1, 2025. After that only pure electric vehicles (aka BEVs) would benefit from the FBT exemption.

The end goal was a quick transition to BEVs. The old argument against the plug-in hybrid was that some overseas studies showed many PHEVs owned by companies did not plug in much.

This was because the employees driving the vehicles typically had fuel cards, which meant they paid nothing for fuel anyway. However, most would have to pay out of their own pocket to charge at home, if charging at home was possible.

Why PHEVs should stay

PHEVs should be included in the novated leasing incentives for three or four more years yet. This is for a couple of reasons, including that it assists manufacturers to achieve their new government mandated vehicle efficiency standards, while it also assists those who regularly travel into regional Australia, where charging infrastructure is not as widespread.

However, the most important reason is because in Australia there are no pure electric vehicle options for entire vehicle segments.

Unlike North America for example, there’s no selection of large pure electric SUVs and utes yet*. This is despite the large SUV, 4WD and ute segment generating huge sales here. In fact, so far even in North America electric vehicles in this category have been expensive, so even if they were available here most would not qualify for the present FBT exemption anyway.

Australian ute drivers have only recently been able to register expressions of interest in the first PHEVs due to arrive in this segment, the Ford Ranger and BYD Shark.

Given the present state of the market, incentivising PHEVs is the only option for this style of vehicle if purchasers are to affordably access cleaner tech and lower fuel bills. Remember, a quality plug-in hybrid ute could easily save tradies a couple of hundred dollars a month in fuel – and emit less CO2!

PHEV sales are now on the rise, with figures from the Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries (FCAI) revealing an increase of over 120 per cent in the first nine months of this year, compared with the same period in 2023.

Given this trend and now with these large 4WD PHEVs getting closer to arrival, it makes no sense that cleaner vehicle incentives are going away at the same time.

Until the advent of much more energy-dense and affordable batteries can give large pure EVs driving ranges comparable to ICE vehicles, the only way to lower the emissions of these larger, heavier vehicles will be to buy those with PHEV technology.

To quote NALSPA CEO Rohan Martin again: “Every PHEV purchased drives down Australia’s total transport emissions and that’s critical for our journey to net zero.”

The journey to net zero component is important, as over here the old argument about people not plugging in carries less weight today.

In Australia, there are simply many more private buyers of utes than in the European markets where the earlier studies were made – and most of these buyers would love to pay less for expensive fuel.

Even today’s commercially owned vehicles have owners looking to lower their fleet costs and meet ESG goals, which novated leasing cleaner vehicles can help achieve.

If there was a requirement to reimburse drivers for charging expenses, even fewer drivers would have problems charging up in this country.

There should also be fewer problems in accessing residential charging in Australia. This is due to lower levels of potentially troublesome apartment ownership (which can bring charging access issues) than was found in European studies.

By taking incentives away from PHEVs next year, the government is going to see fewer people able to afford vehicles that could decrease CO2 emissions and decrease fuel bills.

For purchasers of small- to medium-sized SUVs and sedans this is a lesser problem as there are plenty of affordable BEV options.

Taking incentives away from whole market segments with no selection of BEVs to choose from, however, is just going to see more people buy the cheaper, dirtier vehicles, which is definitely not in the spirit of the original legislation.

*LDV eT60 excepted, but at close to $100k and with a 330km range, unladen, and 1000kg towing capacity it’s not a true replacement for segment benchmarks