The statistics are in and they don’t lie. Australia has recorded its highest annual road toll since 2012, making 2024 the fourth consecutive year in which road fatalities have increased – something that hasn’t happened since 1966, before seatbelts became mandatory in all new cars.

The tragic news of another 1300 road deaths last year comes despite the record number of speed cameras infesting our roads, making them a major source of revenue for state governments, and news that Australia’s most populous state will soon roll out even more of them to target average speed.

It also comes as we approach the halfway mark of the 10‑year National Road Safety Strategy agreed to by Australia’s federal, state and territory governments in 2021, when the road toll spiked from its COVID lockdown low of 1097 the year prior and has continued to increase ever since.

Hundreds of new car deals are available through CarExpert right now. Get the experts on your side and score a great deal. Browse now.

The five main 2030 targets of the government’s current plan to drive down road carnage are reducing road deaths by 50 per cent and serious injuries by 30 per cent from a 2018-2020 baseline; zero road deaths of children aged under seven years; zero road deaths in CBD areas; and zero road deaths on all national highways and high-speed roads – none of which appear likely to be achieved.

A step in the right direction was the long-awaited agreement of all states and territories to share critical road trauma data that could help stem the tide, and the federal government’s funding announcement in November to help them do so, starting with the $21.2 million Road Safety Data Hub website.

It now contains key road fatality statistics for the past 12 months including 483 vulnerable road user deaths (up 9.3 per cent), the fact drivers accounted for the most deaths (45.8 per cent) followed by motorcyclists (21.4 per cent or 278 deaths – up 10.3 per cent on 2023), and that the largest percentage of fatalities (28.5 per cent) occurred in 100km/h zones.

The new database also showed that in 2024 most fatal crashes involved a single vehicle (717, 60.2 per cent), the number of which increased by 40 or 5.9 per cent, while the number of fatal crashes involving multiple vehicles actually decreased.

It also showed that males remain over-represented in road fatalities, but they increased by 1.4 per cent while female fatalities rose by 7.9 per cent; and that the biggest age group represented in road fatalities was 40 to 64-year-olds (up 5 per cent to 400 deaths) followed by people aged 26-39 years – down 2.5 per cent to 273.

Nationally, there were 4.8 road deaths per 100,000 people (an increase of 1.2 per cent), but the Northern Territory topped the charts for the fifth year running with 22.7 deaths per 100,000 people – up a massive 85.6 per cent – followed by Western Australia (6.2 per cent), Tasmania (5.6 per cent), Queensland (5.4 per cent) and the ACT, which at 2.3 per cent per 100,000 population was nevertheless a 170.5 per cent increase from the previous year.

ACT had the lowest number of deaths in the past 12 months with 11 (up 175 per cent), but the next highest increase was in Queensland (up 9.0 per cent) and NSW continued to top the tally at an unchanged 340 fatalities.

As detailed as the data is, road safety groups continue to urge governments at all levels to employ it to better inform transport, infrastructure and policing policies.

“It is clear current road safety approaches are inadequate and that more action is required to save lives,” said Michael Bradley, managing director of the Australian Automobile Association (AAA), the peak body for the nation’s motoring clubs.

“We must use data and evidence about crashes, the state of our roads and the effectiveness of police traffic enforcement to establish what is going wrong on our roads and create more effective interventions.

“This critical data must be embedded into the road funding allocation process so investment can be prioritised to our most dangerous roads.

“Australia’s rising road toll underscores the importance of using road condition data to direct road funding, and to prevent the politicisation of scarce public funds.”

The AAA has called for the introduction of a compulsory safety assessment of roads that are applicable to federal funding, to help determine where the funding should go. It wants the Australian Road Assessment Program (AusRAP) to be used more effectively to improve road safety, by using its engineering analysis of more than 450,000km of Australian roads to determine their safety level, ranked by a star rating system from one to five.

The AAA is right. We need to identify and mitigate the root causes of road fatalities, whether that’s bad road design, poor road maintenance, fatigue, distraction, drink driving, kids in stolen cars, plain old recklessness or, yes, speeding.

There shouldn’t be a single-minded obsession with speed at the expense of actual policing, including a visible police presence and mitigating causes of road rage, such as targeting bad drivers and those who fail to keep left on a multi-lane highway.

Speed cameras don’t do that and they don’t understand good old-fashioned concepts like discretion, appropriate speed and focussing on the road ahead rather than the plethora of posted speed limit signs that seems to litter our roadsides more every day.

But they do rake in plenty of revenue and many states have come to rely on it.

The NSW government made the news in 2021 when it raked in $201 million from more than a million speed camera fines, and last financial year the Queensland government hauled in $464.3 million from its Camera Detected Offence Program (CDOP), the vast majority of which was from fines issued to motorists travelling less than 11km/h above the speed limit.

Queensland doesn’t impose double demerits during public holiday periods like other states do, but it does have some of the world’s most expensive speeding fines. As of mid-2024, low-level speeding – exceeding the speed limit by less than 11km/h – now attracts a $322 fine, while failing to wear a seatbelt or using a mobile phone while driving results in a $1210 fine.

Victoria was the first Australian state to adopt speed cameras, in 1990, and now according to the global Speed Camera Data Base (SCDB) there are 1480 fixed speed and red light cameras nationally, excluding the much larger number of mobile cameras.

The technology was adopted from the UK, which has a population of 67 million and where a network of more than 7000 speed cameras have a tolerance of 10 per cent plus 2mph.

Despite its relatively small population of just 26 million, the SCDB says Australia ranks 14th out of 110 when it comes to the countries with the most speed cameras, and it generates large amounts of revenue thanks to tolerances as low as 2km/h or two per cent for fixed cameras, and 3km/h or three per cent for mobile cameras.

For example, according to the SCDB, the most speed camera-infested route in Australia – a 5.2km stretch in western Sydney, heading northbound from King Georges Road in Beverly Hills – can see motorists accumulate eight demerit points and $1160 in fines in just eight minutes of driving if they travel 9km/h over the posted limit past eight speed cameras, including two school-zone fixed cameras.

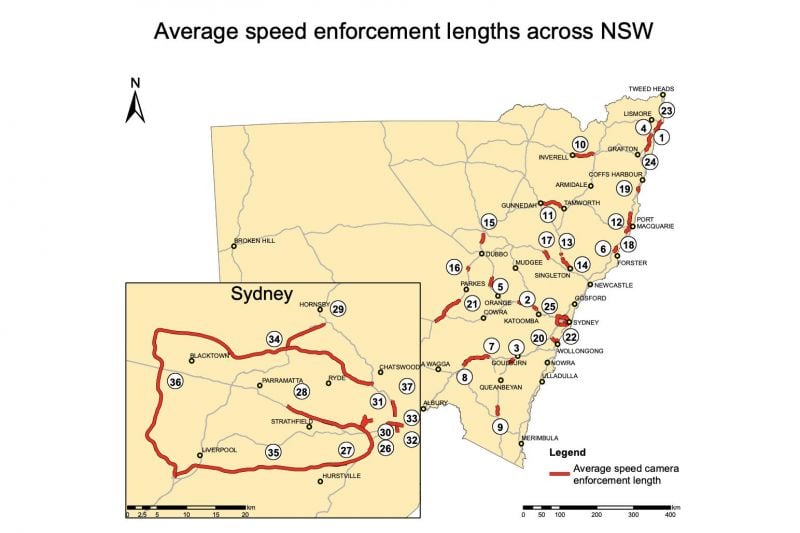

Breaking the speed limit on highways will soon also come under closer scrutiny in NSW, which will join every other mainland state and the ACT in using average speed cameras – also known as point-to-point or time-over-distance cameras – to detect speeding cars as well as trucks.

Average speed cameras have been used for heavy vehicles in NSW since 2010, but the state will trial them for light vehicles from mid-2025, starting with circa-15km high accident zones on the Hume and Pacific Highways.

The trial will include a 60-day warning period during which drivers calculated to have exceeded the speed limit by less than 30km/h will receive warning letters instead of fines, before full enforcement including fines, demerit points and potential license suspensions will take place. Of course, average speed cameras will then be rolled out to other sections of highways in NSW.

The NSW government says speeding remains a leading cause of road fatalities in the state, contributing to around 41 per cent of all road deaths over the past decade. It claims the new average speed camera system “rewards consistent adherence to speed limits rather than slowing down for fixed cameras”.

“Unlike traditional speed cameras, average speed cameras monitor behaviour over extended distances, making it harder for speeding to go unnoticed,” it says.

So it’s clear that speed cameras aren’t going anywhere, despite their failure to curb the road toll. In fact, the number of speed cameras and the revenue they generate in Australia is only set to increase, and low-level speeding appears to be the new target.

At a time when road deaths keep on increasing, this zero-tolerance approach is likely to further undermine the public’s trust in governments and police, and increase the number of private and professional motorists who drive unlicensed and uninsured as it becomes even more difficult to stay within the letter of the law.

MORE: Australia’s 2024 road toll the deadliest in over a decade

MORE: The latest data shows speed cameras don’t save lives

MORE: The real causes of Australian road trauma to be revealed nationally for the first time

MORE: How low-level speeding fines are filling this state’s coffers

MORE: Queensland motorsists to face record fines

MORE: Are speed, mobile phone cameras finally changing behaviour?

MORE: Hold onto your wallets: More cameras coming to Queensland roads

MORE: Hidden school zone speed cameras prove lucrative in first year