Max Davies

2025 BMW 2 Series Gran Coupe review

4 Months Ago

Contributor

Britain and Italy owned the roadster market during the 1960s and ’70s.

The Lotus Elan, Triumph Spitfire, Fiat 124, and Alfa Romeo Spider were known for their open-top thrills and sporty driving performance, but less admired for their reliability and quality problems.

The MX-5 was an attempt by Mazda to capture the spirit behind these cars and blend it with typical Japanese reliability and up-to-date technology.

Mazda wanted to make a car that offered a pure driving experience, but without any of the associated oil leaks and other electrical or mechanical problems.

Part of the credit for the idea behind the MX-5 lies with Bob Hall. Then a motoring journalist with the American publication Motor Trend, Bob admired the classic sports cars described above and pushed Mazda to design its own concept.

Seeing it as an opportunity that could expand sales and improve the company’s image in the US market, Mazda took the idea under consideration, with Bob later working as a product planner for Mazda on the MX-5 program.

At the time, Mazda had three design studios – two in Japan (Hiroshima and Yokohama) and one in America (Irvine, California). The company organised an internal competition between these studios for design proposals.

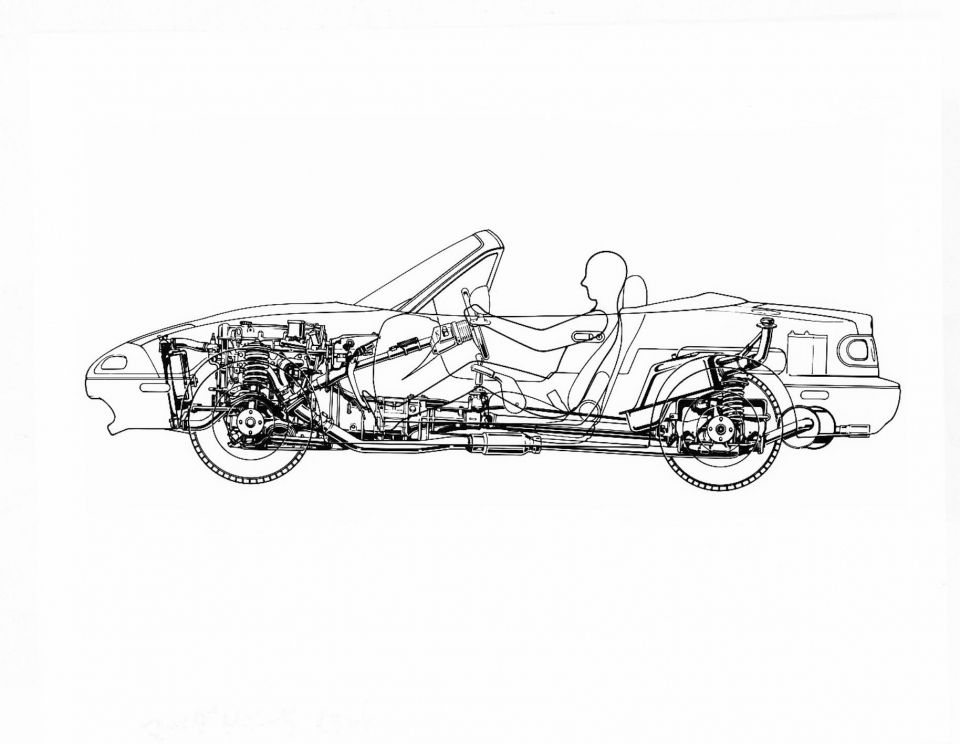

Hiroshima and Yokohama went ahead with a front engine, front-wheel drive (FF) and mid-engine, rear-wheel drive drivetrain (MR) respectively, while the Californian studio adopted a design based on a front engine, rear-wheel drive (FR) layout.

The American proposal won out, with full-size clay models being completed in 1984 and the production model being revealed five years later at the 1989 Chicago motor show.

At launch the MX-5 featured a 1.6L four cylinder engine providing 86 kW of power and 136 Nm of torque, mated to a five-speed manual transmission.

With a 50:50 weight distribution front to rear, the MX-5 weighed only 980 kg, had a length of under four metres (3970 mm), and could sprint to 100 km/h in approximately 9.5 seconds.

Over a production span of nine years (1989-1997), Mazda produced over 420,000 examples of the original MX-5.

A word on the nomenclature. The MX-5 stands for Mazda Experiment, project number 5, but the MX-5 name is only used in Europe and Australia.

Mazda’s marketing team believed American consumers preferred their cars to have proper names rather than an alphanumeric model designation, and so added the word ‘Miata’ (meaning ‘reward’ in Old High German) as a suffix.

In Japan, Mazda at the time was in the process of launching its now-defunct Eunos luxury brand, and so the MX-5 was initially known as the ‘Eunos Roadster.’

Like its spiritual European predecessors, a key aspect of the MX-5 design brief was to be affordable, but offer a driver-focused experience. Mazda expressed this succinctly through the ‘jinba ittai’ philosophy behind the car.

Japanese for ‘horse and rider as one’, Mazda removed all unnecessary fripperies and excess costs and weight, in an effort to ensure that the fundamentals that remained were executed perfectly and provided a real sense of connection to the driver.

Parts sharing and reducing the cost of individual components was key to this. The MX-5 adopted wheels from the Mazda 323, whilst the transmission was borrowed from the larger RX-7, but modified with altered gear ratios and a shorter throw to deliver its signature feel.

To maintain an excellent ride and handling balance, the MX-5 featured all-round double wishbone independent suspension. Rather than using lighter (but more expensive) aluminium, however, the MX-5 stuck with cheaper steel wishbones.

A key innovation for the car’s chassis was the development of a special Power Plant Frame (PPF) to improve vehicle stiffness, and thereby improve handling responsiveness and ride quality. The PPF was a truss-like structure that encapsulated the differential, and improved rigidity to minimise flex.

In line with its affordable price (starting at $29,550 for a base model in 1989 in Australia), the MX-5 sported an exterior design designed to convey a fun and accessible character.

Trendy pop-up headlights were fitted, and together with the smooth side profile created a friendly, almost pebble-like rounded look.

The convertible soft-top was not stored under a tonneau cover, which ensured that it could be easily and quickly operated manually, simply through the driver reaching over their shoulder and pulling up the soft-top.

Where expert car reviews meet expert car buying – CarExpert gives you trusted advice, personalised service and real savings on your next new car.

Max Davies

4 Months Ago

William Stopford

2 Months Ago

Alborz Fallah

1 Month Ago

James Wong

25 Days Ago

Paul Maric

15 Days Ago

William Stopford

11 Days Ago